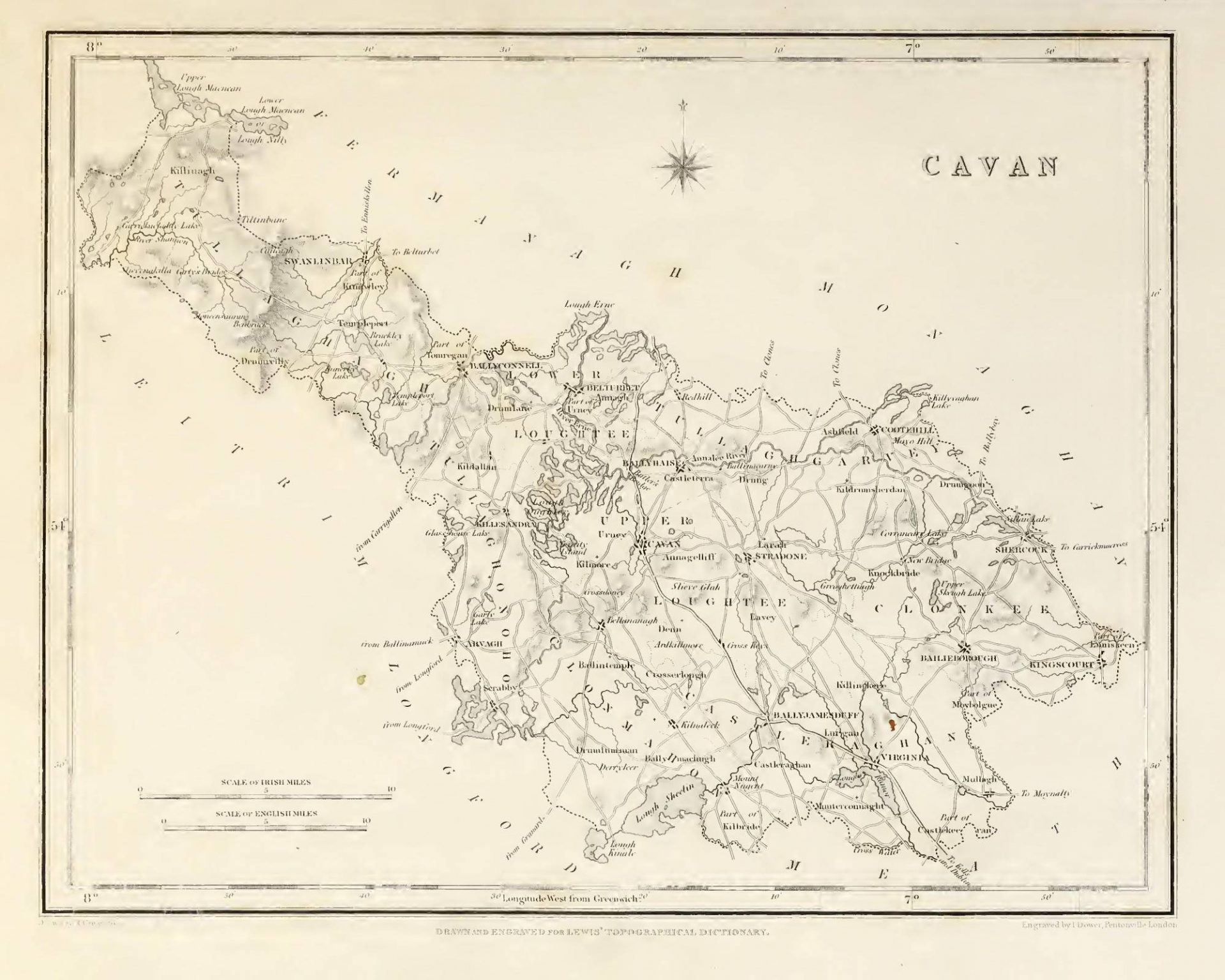

CAVAN (County of), an inland county of the province of Ulster, hounded on the north by the county of Fermanagh; on the west, by that of Leitrim; on the south, by those of Longford, Westmeath, and Meath; and on the east and north-east, by that of Monaghan. It extends from 53° 43′ to 54° 7′ (N. Lat.) and from 6° 45′ to 7° 47′ (W. Lon.); and comprises 477.360 statute acres, of which 375,473 are arable land, 71.918 uncultivated, 7325 plantations, 502 under towns and villages, and 22,142 water. The population, in 1821 was 195,076; in 1831, 228,050; and in 1841, 243,158.

According to Ptolemy, this tract, with the districts included in the adjacent counties of Leitrim and Fermanagh, was occupied by the Erdini, designated in the Irish language Ernaigh, traces of which name are yet preserved in that of Lough Erne and the river Erne, upon which and their tributaries to these districts border. This district, exclusively of the greater part of the present county of Fermanagh, formed also the ancient principality of Breghne, Brefine, Breifne, Breffny, or Brenny, as it has been variously spelt, which had recognised limits from time immemorial, and was divided into the two principalities of Upper or East Breifne and Lower or West Breifne, the former composed almost entirely of the present county of Cavan, and the latter of that of Leitrim. East Breifne was often called Breifne O’Reilly, from its princes or chiefs having from remote ages borne that name: these chiefs were tributary to the O’Nial of Tiroen long before the arrival of the English, although Camden says that in his time they represented themselves as descended from the English family of Ridley. The county is celebrated in the history of the wars in Ireland for the fastnesses formed by its woods, lakes, and bogs, which long secured the independence of its native possessors. Cavan was one of the counties formed in Ulster, in 1584, by Sir John Perrott, lord-deputy of Ireland, and derived its name from the principal seat of its ancient rulers, which is still the provincial capital: in the following year it was represented in a parliament held in Dublin, by two loyal members of the family of O’Reilly. Both Breffnys had anciently formed part of Connaught, but the new county was incorporated with Ulster. The O’Reillys were at this time a warlike sept, particularly distinguished for their cavalry, and not living in towns, but in small castles scattered over the country. In order to lessen their influence by partitioning it among different leaders, and thus reduce them to the English law, it was resolved to divide the country into baronies and settle the proprietorship of each exclusively on a separate branch of the families of the former proprietors. Sir John O’Reilly, then chief lord of the country, had, indeed, covenanted to surrender the whole to Queen Elizabeth, and on the other part Sir John Perrott had covenanted that letters-patent should be granted to him of the whole; but this mutual agreement led to no result, and commissioners were sent down to carry the division into effect. By them the whole territory was partitioned into seven baronies, of which, two were assigned to Sir John O’Reilly free of all contributions; a third was allotted to his brother, Philip O’Reilly; a fourth to his uncle Edmond; and a fifth to the sons of Hugh O’Reilly, surnamed the Prior. The other two baronies, possessed by the septs of Mac Kernon and Mac Gauran, and remotely situated in the mountains and on the border of O’Rorke’s country, were left to their ancient tenures and the Irish exactions of their chief lord, Sir John, whose chief-rent out of the other three baronies not immediately possessed by him was fixed at 10s. per annum for every pole, a subdivision of land peculiar to the county and containing about 25 acres: the entire county was supposed to contain 1620 of these poles.

But these measures did not lead to the settlement of the country; the tenures remained undetermined by any written title; and Sir John, his brother, and his uncle, as successive tanists, according to the ancient custom of the country, were all slain while in rebellion. After the death of the last, no successor was elected under the distinguishing title of O’Reilly, the country being broken by defeat, although wholly unamenable to the English law. Early in the reign of James I., the lord-deputy came to Cavan, and issued a commission of inquiry to the judges then holding the assize there, concerning all lands escheated to the crown by attainder, outlawry, or actual death in rebellion; and a jury of the best knights and gentlemen that were present, and of whom some were chiefs of Irish septs, found an inquisition; first, concerning the possessions of various freeholders slain in the late rebellion under the Earl of Tyrone, and secondly, concerning those of the late chiefs of the country who had shared the same fate; though the latter finding was obtained with some difficulty, the jurors fearing that their own tenures might be invalidated in consequence. Nor was this apprehension without foundation; for, by that inquisition, the greater part, if not the whole, of the county, was deemed to be vested in the crown, and the exact state of its property was thereupon carefully investigated.

This inquiry being completed, the king resolved on the new plantation of Ulster, in which the plan for the division of this county was as follows. The termon or church lands, in the ancient division had been 140 poles, or about 3500 acres, which the king reserved for the bishop of Kilmore; for the glebes of the incumbents of the parishes to be erected, were allotted 100 poles, or 2500 acres; and the monastery land was found to consist of 20 poles, or 500 acres. There then remained to be distributed to undertakers 1360 poles, or 34,000 acres. These, after deducting 60 poles hereafter mentioned, were divided into 26 proportions; 17 of 1000 acres each, five of 1500, and four of 2000; each of which was to be a parish, and to have a church erected upon it, with a glebe of 60 acres for the minister in the smallest proportions, of 90 in the next, and of 120 in the largest. To British planters were to be granted six proportions, viz., three of the least, two of the next, and one of the largest, and in these were to be allowed only English and Scottish tenants; to servitors were to be given six other proportions, three of the least, two of the middle, and one of the largest, to be allowed to have English or Irish tenants at choice; and to natives, the remaining fourteen, being eleven of the least, one of the middles, and two of the greatest size. There then remained 60 poles or 1500 acres. Of these, 30 poles, or 750 acres, were to be allotted to three corporate towns or boroughs, which the king ordered should be endowed with reasonable liberties, and send burgesses to parliament, and each of which was to receive a third of this quantity; 10 other poles, or 250 acres, were to be appendant to the castle of Cavan; 6 to that of Cloughoughter; and the remaining 14 poles, or 346 acres, were to be for the maintenance of a free school to be erected in Cavan. Two of the boroughs that were created and received these grants were Cavan and Belturbet, and the other 250 acres were to be given to a third town, to be erected about midway between Kells and Cavan, on a site to be chosen by the commissioners appointed to settle the plantation; this place was Virginia, which, however, never was incorporated. The native inhabitants were awed into acquiescence in these arrangements; and such as were not freeholders under the above grants, were to be settled within the county, or removed by order of the commissioners. The lands thus divided were then profitable portions, and to each division a sufficient quantity of bog and wood was super-added. A considerable deviation from the project took place in regard to tithes, glebes, and parish churches. A curious record of the progress made by the undertakers in erecting fortified houses, &c, up to the year 1618-19, is preserved in Pynnar’s Survey; the number of acres enumerated in this document amounts to 52,324, English measure, and the number of British families planted on them was 386, who could muster 711 armed men. Such was the foundation of the rights of property and of civil society in the county of Cavan, as existing at the present day; though not without subsequent disturbance; for both O’Reilly, representative of the county in parliament, and the sheriff his brother, were deeply engaged in the rebellion of 1641. The latter summoned the Roman Catholic inhabitants to arms; they marched under his command with the appearance of discipline; forts, towns, and castles were surrendered to them; and Bedel, Bishop of Kilmore, was compelled to draw up their remonstrance of grievances, to be presented to the chief governors and council.

Cavan is partly in the diocese of Meath, and partly in that of Ardagh, but chiefly in that of Kilmore, and wholly in the ecclesiastical province of Armagh. For CIVIL purposes, it is divided into the eight baronies of Castleraghan, Clonmahon, Clonkee, Upper Loughtee, Lower Loughtee, Tullaghgarvey or Tullygarvey, Tullaghonoho or Tullyhunco, and Tullaghagh or Tullyhaw. It contains the disfranchised borough and market towns of Cavan and Belturbet; the market and post towns of Arvagh, Bailieborough, Ballyconnell, Ballyhaise, Ballyjamesduff, Cootehill, Killesandra, Kingscourt, Stradone, and Virginia; the market towns of Ballinagh and Shercock; the post towns or villages of Crossdoney, Mount-Nugent, and Scrabby; the modern and flourishing town of Mullagh; and, among the villages, those of Butlersbridge and Swanlinbar. Prior to the Union it sent six members to the Irish parliament, two for the county at large, and two for each of the boroughs of Cavan and Belturbet; but since that period its only representatives have been the county members returned to the Imperial parliament, and elected at Cavan. The constituency, as registered in 1843, amounted to 2056, of whom 276 were £50, 149 £20, and 1494 £10, freeholders; 21 £20, and 111 £10, leaseholders; and 5 rent-chargers. The county is in the north-west circuit: the assizes are held at Cavan, in which are the county court-house and gaol. Quarter-sessions are held in rotation at Cavan, Bailieborough, Ballyconnell, and Cootehill; and there are a sessions-house and bridewell at each of the three last-named towns. The number of persons charged with criminal offences and committed to prison, in 1841, was 564. The local government is vested in a lieutenant, 12 deputy-lieutenants, and 76 other magistrates, besides the usual county officers, and a coroner. There are 23 constabulary police stations, having in the whole a force of a county inspector, 7 sub-inspectors, 9 head constables, 30 constables, 146 sub-constables, with 9 horses; the expense of whose maintenance, in 1842, was £9782, defrayed equally by grand jury presentments and by government. The county infirmary, and one of the four fever hospitals, are at Cavan; and there are 20 dispensaries, situated respectively at Arvagh, Bailieborough, Ballyjamesduff, Ballyconnell, Belturbet, Ballymacue, Ballinagh, Ballyhaise, Butler’s-Bridge, Cootehill, Crossdoney, Cavan, Killesandra, Kingscourt, Mount-Nugent, Mullagh, Shercork, Swanlinbar, Stradone, and Virginia; all of which are maintained partly by grand jury presentments and partly by voluntary contributions, in equal portions. The amount of grand jury presentments, for 1844, was £23,850. Cavan, in military arrangements, is included in the Belfast district, and contains the stations of Belturbet and Cavan, the former for cavalry and the latter for infantry, which afford unitedly accommodation for 13 officers, 286 men, and 101 horses.

The county lies midway in the island between the Atlantic Ocean and the Irish sea, its two extreme points being about 20 miles distant from each. The surface is very irregular, everywhere varied with undulations, of hill and dale, occasionally rocky, and with scarcely a level spot intervening; but the only mountainous elevations are situated in the northern extremity. To the north-west the prospect is bleak, dreary, and much exposed: in other parts, however, the county is not only well sheltered and woody, but the scenery is highly picturesque and attractive: numerous lakes of great extent and beauty adorn the interior; and generally, the features of the country are strikingly disposed for landscape decoration. Yet these natural advantages are but partially improved, though in no part of Ireland are there demesnes of more magnificence. The scenery of the lakes is varied by beautiful islands; and lofty wood overhang the river Erne, which flows into the celebrated lake of that name in the neighbouring county of Fermanagh. Bruce Hill forms a striking object in the southern extremity of the county; the Leitrim mountains overlook its western confines; while towards the north-west rises the bleak, barren, and lofty range of the Silver-Russell mountains. But the chief mountains are those which separate this county and province from Connaught, encircling Glangavlin; namely the Lurganculliagh, the Coilcagh, Slievenakilla, and the Mullahuna, the highest of which is 2185 feet above the level of the sea. Some of the lakes cover many hundred acres, while several of the smaller are nearly dry in summer, and might be effectually drained; all abound with fish, and their waters are remarkably clear. The streams issuing from some of them, flow through the vales with much rapidity; their final destination is Lough Erne or Lough Ramor. A ridge of hill crosses the county nearly from north to south, dividing it into two unequal portions: on the summit, near Lavy chapel, is a spring, a stream descending from which takes an eastern course towards Lough Ramor, and into the Boyne, which empties itself into the Irish sea in Drogheda harbour; another stream flows westward through Lough Erne into the Atlantic, on the coast of Donegal. From the elevation and exposure of the surface, the climate is chilly, though at the same time salubrious, the exhalations from the numerous lakes are dispelled by the force of the gales. The soil in its primitive state is not fertile, being cold, in many places spongy, and inclined to produce rushes and a spiry aquatic grass; it commonly consists of a thick stratum of stiff brown clay over an argillaceous substratum; but when improved by draining and the application of gravel or lime, it affords a grateful return of produce. In the vales is found a deep brown clay, forming excellent land for the dairy.

AGRICULTURE, long neglected, has at length attracted the attention of landlords. The chief crops are oats and potatoes; in some districts a considerable quantity of flax is cultivated, and wheat, within the last two or three years, has become more common. Green crops, hitherto seldom or never grown, except by some of the nobility and gentry, are now more generally raised. Lord Farnham has in cultivation a large and excellent farm; and around Virginia, the Marquess of Headfort’s property, they are evidences of a superior system of husbandry; but it is in the neighbourhood of Bailieborough, on Sir William Young’s and Sir George Hodson’s estates, that agriculture has made the most rapid strides within the last ten years. Other landowners also afford by example every inducement to agricultural improvement. The iron plough has been generally substituted for spade labour, by which the land was formerly almost exclusively cultivated. Into the mountain districts, however, neither the plough nor wheel-car has yet found its way; the spade, sickle, and flail are the chief agricultural implements; cattle and pigs are the common farm stock; and oats and potatoes are the prevailing crops. The sides of the mountains are usually cultivated for oats to a considerable height; and their summits are grazed by herds of small young cattle. These practices are more especially prevailed within the barony of Tullaghagh, in the mountain district between the counties of Fermanagh and Leitrim, generally known as “the kingdom of Glan”, but more properly called Glangavlin, or “the country of the Mac Gaurans.” To this isolated district, there is no public road, and only one difficult pass; in some places a trackway is seen, by which the cattles are driven out to the fairs of the adjacent country. It is about 16 miles in length by 7 in breadth, and is densely inhabited by a primitive race of Mac Gaurans and Dolans, who intermarry, and observe some peculiar customs; they elect their own king and queen from the ancient race of the Mac Gaurans, to whom they pay implicit obedience. Tilling the land and attending the cattle constitute their sole occupation; potatoes and milk, with, sometimes, oaten bread, are their chief food; and the want of a road by which the produce of the district might be taken to the neighbouring markets, operates as a discouragement to industry, and an incentive to the illicit application of their surplus corn.

Wheat might be advantageously cultivated in most of the southern parts of the county, by draining and properly ploughing the land: a great defect consists in not ploughing sufficiently deep, from which cause the grain receives but little nourishment; the land soon becomes exhausted, and is allowed to recover its productiveness by natural means. Hay seeds are scarcely ever sown. Barley is sometimes raised, and the crop is generally good. In consequence of the system here practised of shallow ploughing, and owing to the unchecked growth of weeds, flax does not flourish in this so well as in some of the other northern counties; but it is still an amply remunerative crop. The fences in most parts are bad, consisting chiefly of a slight ridge of earth loosely thrown up. Draining and irrigation were until lately almost wholly unpractised; but the principal landowners are now carrying out the best system of draining, to a great extent, and with much success; and no county in Ireland has latterly made more improvement in these two respects. The country offers facility for both; the gentle elevations are generally dry, and afford, beneath the surface, stones for draining; while the low grounds abound with springs, whose waters may be applied to the beneficial purposes of irrigation. Large allotments in the occupation of one individual are found in the mountainous districts, and are appropriated to the grazing of young cattle during the summer months. In the demesnes of the gentry, some sheep are fattened; but there are no good sheepwalks of any extent, except in the neighbourhood of Cavan, which district, indeed, is so superior to any other part of the county for fattening, that oxen are fed to as great size as in any part of Ireland. Dairy-farms are by no means numerous, although the butter of Cavan is equal to that of any other part of the kingdom.

The breed of Cattle varies in almost every barony: that best adapted to the soil is a cross between the Durham and the Kerry, but the long-homed attains the greatest size. In the mountain districts the Kerry cow is the favourite; and in the lower or central parts, around Cavan, are some very fine Durham cattle and good crosses with the Dutch. The Sheep are mostly a cross between the New Leicester and the old sheep of the country; the fleece, though mostly light, is good, and the mutton of excellent flavour. The Horses are a light, hardy, active breed, well adapted to the country. The breed of Pigs has been much improved, and although they do not attain a large size, they are profitable, and readily fatten. Lime is the general Manure, although in some parts the farmer has to draw it many miles; and calcareous sand and gravel, procured from the Escars in the baronies of Tullaghonoho and Loughtee, are conveyed for that use to every part of the county where the roads permit, and sometimes even into the hilly districts by means of two boxes, called “bardoes”, slung across the back of a horse, which is the only means of conveyance the inhabitants of those parts possess. The Woods were formerly very considerable, and the timber of uncommon size, as is evinced by the immense trees found in the bogs; but demesne grounds only are now distinguished by this valuable ornament. There are, however, numerous and extensive plantations in several parts, which in a few years will greatly enrich the scenery, particularly around the lakes of Ramor and Shellin; also near Stradone, Ballyhaise, Ballymacue, Fort Frederic, Farnham, Killesandra, and other places. The county contains Bogs of sufficient extent for supplying its own fuel, and of a depth everywhere varying, but generally extremely great: they commonly lie favourably for draining, and the peat yields strong red ashes, which form an excellent manure. There is likewise a small proportion of moor, having a boggy surface, and resting on partial argillaceous strata: in these a marl, highly calcareous and easily raised, most commonly abounds. The fuel in universal use is peat.

The minerals are, iron, lead, silver, coal, ochres, marl, fullers-earth, potters-clay, brick-clay, manganese, sulphur, and species of jasper. Limestone, and various kinds of good building-stone, are also procured, especially in the north-western extremity of the county, which comprises the eastern part of the great Connaught coal-field. A very valuable white freestone, soft to work but exceedingly durable, is found near Ballyconnell, and at Lart, one mile from Cavan. The substratum around the former place is mostly mountain limestone, which dips rapidly to the west, and appears to pass under the Slieve-Russell mountains, a range composed of the new red sandstone formation, with some curious amalgamations of greenstone. To the west of Swanlinbar rise the Bealbally mountains, through which is the Gap of Beal, the only entrance to Glangavlin; and beyond, at the furthest extremity of the county, is Lurganculliagh, forming the boundary between Ulster and Connaught. The base of this mountain range is clay-slate; the upper part consists entirely of sandstone, and near the summit is a stratum of mountain coal, ten feet thick, in the centre of which is a vein of remarkably good coal, but only about eight inches in thickness. The coal is visible on the eastern face of the mountain, at Meneack, in this county, where some trifling workings have been made, to which there is not even a practicable road. its superficial extent is supposed to be about 600 acres. The sandstone of these mountains, in many parts, forms perpendicular cliffs of great height; and the summit of Cuilcagh, which is entirely composed of it, resembles an immense pavement, traversed in every direction by great fissures. Frequently, at the distance of 80 to 100 yards from the edge of the precipice, are huge chasms, from twelve to twenty feet wide, extending from the surface of the mountain to the bottom of the sandstone. Some of the calcareous hills to the west of the valley of Swanlinbar rise to a height of 1500 feet, and are overspread with large rolled masses of sandstone, so as to make the entire elevation appear at first sight as if composed of the same. Iron-ore abounds among the mountains of this part of the county, and was formerly worked. A lead-mine was wrought some years ago near Cootehill, and lead and silver ore are met with in the stream descending from the mountain of Ortnacullagh, near Ballyconnell. In the district of Glan is found pure native sulphur in great quantities, particularly near Legnagrove and Dowra, and fullers-earth and pipe-clay of superior quality exist in many parts. Proceeding towards the Fermanagh mountains, beautiful white and red transparent spars are found within a spade’s depth of the surface; and here are two quarries of rough slate. Potters’ clay, in this part of the county, occurs in every townland, and some of it is of the best and purest kind; patches of brick clay of the most durable quality are also common.

The chief MANUFACTURE is that of linen, upon which the prosperity of the inhabitants much depends, as it is carried on in almost every family. The average quantity of linen annually manufactured, and sold in the county, was estimated, at the commencement of the present century, to amount in value to £70,000; and pieces to the value of above £20,000 more were carried to markets beyond its limits. The number of bleaching establishments at the same period was twelve, in which about 91,000 pieces were annually finished. The quantity of linen manufactured at present is much greater, but the article is considerably reduced in price. Some of the bleach-greens are out of work; yet from the improvement of the process, a far greater number of webs is now bleached than was formerly; in a recent year, nearly 150,000 pieces were finished, mostly for the English market. These establishments, around which improvements are being made every year, and which diffuse employment and comfort among a numerous population, are principally in the neighbourhoods of Cootehill, Tacken, Cloggy, Bailieborough, Serabby, and Killiwilly. Frieze is made for home use, especially in the thinly-peopled barony of Tullaghagh. The commerce of the county is limited and of little variety: its markets are remarkable only for the sale of yarn, flax, and brown linen; the principal are those of Cootehill and Killesandra.

Among the chief rivers is the Erne, which has its source in Lough Granny, near the foot of Bruce hill, on the south-western confines of the county; it pursues a northern course into Lough Oughter, and hence winds in the same direction by Belturbet into Lough Erne, which, at its head, forms the northern limit of the county. In most other parts the waters, consisting of numerous lakes and their connecting streams, are tributary to the Erne. The SHANNON has its source in a very copious spring, called the Shannon Pot, at the foot of the Cuilcagh mountain, in Glangavlin, in the townland of Derrylaghan, four miles south of the mountain road leading from Enniskillen to Manor-Hamilton, and nine miles north of Lough Allen: from this place to Kerry Head, where it falls into the sea, it pursues a course of 243 miles. it is navigable 234 miles, and during that distance has a fall of not more than 148 feet. It bounds or passes through eleven counties; Cavan, Leitrim, Longford, Westmeath, King’s county, Roscommon, Tipperary, Galway, Limerick, Clare, and Kerry. The main tributaries of this river are, the Buella, in Roscommon county; the Camlin and the Inny, in Longford county, the Suck, in Roscommon and Galway; the Brosna, in the King’s county; the Lower Brosna, in Tipperary and King’s county; the Maig, in Limerick county; the Bunratty and the Fergus, in Clare; and the Askeaton, in Limerick; besides innumerable streams, some with, and others without, names. It expands into five different loughs, as follows: Lough Allen, in Leitrim county; Lough Boderig and Lough Boffin, in Roscommon county; Lough Ree, in Westmeath; and Lough Derg, in Tipperary. The principal islands on its waters are, Cloondra, in Longford county, Foynes, in Limerick, Scattery, in Clare; and Carrigue, in Kerry county. The chief towns and villages by which it passes are, Ballintra, Leitrim, Carrick-on-Shannon, Jamestown, Drumsna, and Ruskey, in Leitrim county; Newtown-Forbes, Tarmonbarry, and Lanesborough, in Longford county; Athlone, in Roscommon and Westmeath counties, Shannon-Bridge and Banagher, in King’s county; Portumna, in Galway county; Killaloe, O’Brien’s-Bridge, Bunratty, and Kilrush, in Clare county; Limerick city, and Glin, in the county of Limerick; and Tarbert and Ballylongford, in Kerry county. Of late years, the attention of the legislature has been given to the improvement of this noble river. Other notices of its course will be found in the articles on counties which it bounds. The Shannon confers the title of Earl on the family of Boyle, by creation, 17th April, 1756.The Rlacktrater has its source in a lake at Bailieborough Castle, and flows on by Virginia into Lough Ramor, whence it enters the county of Meath, and becomes a tributary to the Boyne. A line of artificial navigation has been proposed from Belturbet, by Cootehill, into the county of Monaghan.

The old lines of roads within the county are injudiciously formed, so as to encounter the most formidable hills, and although the new lines are made to wind through the valleys; yet with the exception of those very recently made, they are of inferior construction. The material formerly used was clay-slate, which pulverised in a short time, but, since the Grand Jury act came into operation, the lines have been well laid out, and the only material now used is limestone or greenstone. Several important lines have been formed, and others are in progress or contemplated: among the roads which promise to be of the greatest advantage are those through the wild and mountainous district of Glangavlin; they are all made and kept in repair by grand jury presentments.

The remains of antiquity are comparatively few and uninteresting. The most common are cairns and raths, the latter of which are particularly numerous in the north-eastern part of the county, and near Kingscourt: in one at Rathkenny, near Cootehill, was found a considerable treasure, together with a gold fibula. There are remains of a round tower of inferior size at Drumlane. The number of abbeys and priories was eight, the remains of none of which, except that of the Holy Trinity, now exist, so that their sites can only be conjectured. Few also of the numerous castles remain, and all, except that of Cloughoughter, are very small. Though there are many good residences surrounded with ornamented demesnes, the seats of the nobility and gentry are not distinguished by any character of architectural magnificence; the chief are noticed under the heads of the parishes in which they are respectively situated. The more substantial farmers have good family house; but the dwellings of the peasantry are extremely poor, and their food consists almost entirely of oatmeal, milk, and potatoes. The English language is generally spoken, except in the mountain districts towards the north and west, and even there it is spoken by the younger part of the population, though the aged people all speak Irish, particularly in the district of Glan. With regard to fish, the lakes afford an abundance of pike, eels, and trout; and cod, salmon, and herrings, are brought in abundance by hawkers. The chief natural curiosities are the mineral springs: the most remarkable are those at Swanlinbar and Derrylyster, the waters of which are alterative and diaphoretic; those at Legnagrove and Dowra, containing sulphur and purging salt, and are used in nervous diseases; the well at Owen Broun, which has similar medicinal properties; and the purgative and diuretic waters of Carrickmorc, which are impregnated with fixed air and fossil alkali. The mineral properties of a pool in the mountains of Loughlinlca, between Bailieborough and Kingscourt, are also very remarkable. In 1617, Sir Oliver Lambart was created baron of Cavan, and this title was raised to an earldom in favour of his son Charles, by whose lineal descendants it is still enjoyed; the former nobleman was a distinguished soldier, and the latter a leading member and principal speaker in the Irish house of lords.

Leave a reply