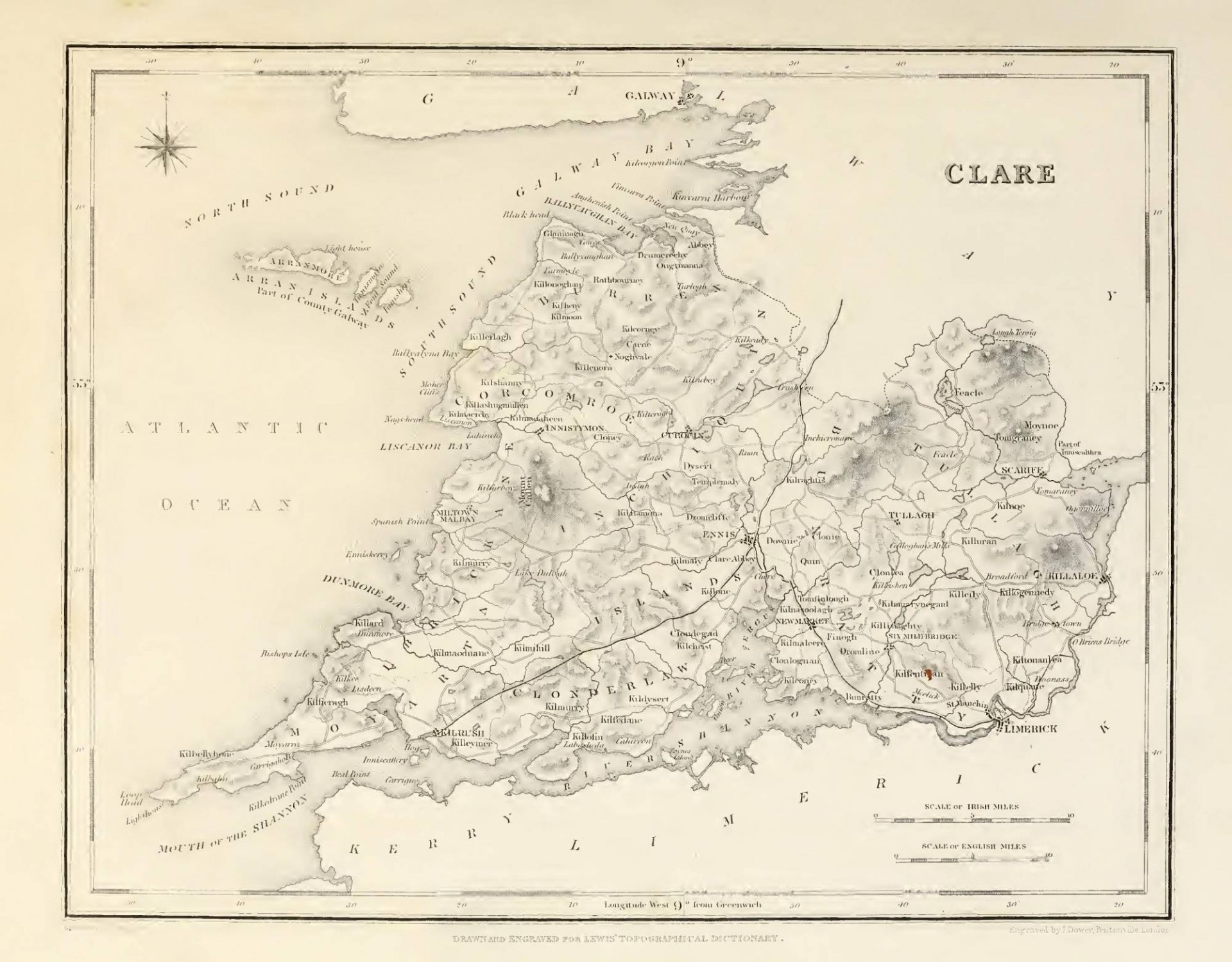

CLARE (County of), a maritime county of the province of MUNSTER, bounded on the east and south by Lough Derg and the river Shannon, which successively separate it from the counties of Tipperary, Limerick, and Kerry ; on the west by the Atlantic Ocean , and on the north-west by Galway bay ; while on the north and north-east an imaginary boundary divides it from the

county of Galway. It extends from 52° 30′ to 53° (N. Lat.) and from 8° 15′ to 9° 30′ (W. Lon.) ; and comprises 827.994 statute acres, of which 455,009 are arable land, 296,033 uncultivated, 8304 plantation, 79.8 under towns and villages, and 67,920 water. The population, in 1821, was 208,089; in 1831, 258,262 ; and in 1841, 286,394.

The inhabitants of this tract, in the time of Ptolemy, were designated in the Latin language Gangani, and are represented as inhabiting also some of the southern parts of the modern county of Galway : in the Irish language their appellation was Siol Gangain ; and they are stated, both by Camden and Dr. Charles O’Conor, to have been descended from the Coneani of Spain. The present county formed from a very early period a native principality, designated Tuath-Mumhan, or Thomond, signifying ” North Munster ;” and contained the six cantreds of Hy Lochlean, Corcumruadh, Ibh Caisin, Hy Garman, Clan Cuilean, and Dal Gaes. In Hy Lochlean, or Bhurrin, the present barony of Burren, the O’Loghlins or O’Laghlins were chiefs ; in Corcumruadh, the modern Corcomroe, lived the O’Garbhs, although that portion is stated by Ware to have been occupied by the septs of O’Connor and O’Loghlin ; in Ibh Caisin, the present Ibrickane, were the Cumhead-mor O’Briens, this being the hereditary patrimony of the O’Briens or O’Bricheans ; in Hy Garman, the modern Moyarta, the O’Briens Arta ; and in Clan Cuilean, the present Clonderlaw, the Mac Namaras. Dal Gaes comprised the more extensive districts included in the baronies of Inchiquin, Bunratty, and Tulla, forming the entire eastern half of the present county ; and was ruled by the O’Briens, who exercised a supreme authority over the whole, and who preserved their ascendancy here from the date of the earliest records to a late period. Few have more honourably distinguished themselves in the annals of their country than these chiefs and their brave Dalcassian followers, especially in the wars against the Danes, who long oppressed this county with their devastations, and formed permanent stations on the Shannon, at Limerick and Inniscattery. From these stations and from the entire district the Danes were, however, finally expelled, early in the 11th century, by the well-directed efforts of the great Brien Boroihme, the head of this sept, and monarch of all Ireland, whose residence, and that of his immediate successors, was at Kinkora, near Killaloe.

About the year 1290, the Anglo-Norman invaders penetrated into the very heart of Thomond, and in their progress inflicted the most barbarous cruelties especially upon the family of O’Brien ; but they were compelled to make a precipitate retreat on the advance of Cathal, Prince of Connaught. De Burgo, in the year 1200, also harassed this province from Limerick ; and William de Braos’ received from King John extensive grants here, from which, however, he derived but little advantage. Donald O’Brien, amid the storms of war and rapine that laid waste the surrounding parts of Ireland, was solicitous for the security of his own territories, and, as the most effectual method, petitioned for, and obtained from Henry III., a grant of the kingdom of Thomond, as it was called, to be held of the king during his minority, at a yearly rent of £100, and a fine of 1000 marks. Nevertheless, Edward I., by letters-patent dated Jan. 26th, 1275, granted the whole land of Thomond to Thomas de Clare, son of the Earl of Gloucester, who placed himself at the head of a formidable force to support his claim. The O’Briens protested loudly against the encroachment of this new colony of invaders. In a contest which speedily ensued, the natives were defeated, and the chief of the O’Briens slain; but with such fury was the war maintained by his two sons, that the new settlers were totally overthrown, with the loss of many of their bravest knights : De Clare and his father-in-law were compelled to surrender, after first taking shelter in the fastnesses of an inaccessible mountain ; and the O’Briens were acknowledged sovereigns of Thomond, and acquired various other advantages. De Clare, however, afterwards attempted with some success, to profit by the internal dissensions of the native septs. He died in 1287. at Bunratty, seised, according to the English law, of the province of Thomond, which descended to his son and heir, Gilbert de Clare, and, on the death of the latter without issue, to Richard de Clare. The O’Briens being subdued by Piers Gaveston, Richard de Clare extended his power in this province, where, in 1311, he defeated the Earl of

Ulster, who had commenced hostilities against him. But shortly after, the English received a defeat from the O’Briens, and de Clare, who died in 1317, had no English successor in the territories. Of the settlements made by these leaders, the principal were Bunratty and Clare, long the chief towns of the district ; and the English colonists still maintained a separate political

existence here ; for so late as 1445, we find the O’Briens making war upon those not yet expelled. All of them, however, were eventually put to the sword, driven out. or compelled to adopt the manners of the country ; the entire authority reverting to the ancient septs, among

whom the Mac Mahons rose into some consideration.

In the reign of Henry VIII., Murchard or Murrough O’Brien was created Earl of Thomond for life, with remainder to his nephew Donogh, whose rights he had usurped, and who was at the same time elevated to the dignity of Baron Ihrakin. Murrough was also created Baron Inchiquin, with remainder to the heirs of his body ; and from him the present Marquess of Thomond traces his descent. On the division of Connaught into six counties by Sir Henry Sidney, then lord-deputy, in 1565, Thomond, sometimes called O’Brien’s country, was also made shire ground, and called Clare, after its chief town, and its ancient Anglo-Norman possessors. In 1599 and 1600, Hugh O’Donell plundered and laid waste the whole county: Teg O’Brien entered into rebellion, ton was shortly after slain. In accordance with its natural position, the county, on its first erection, was added to Connaught ; but subsequently, in 1602, it was re-annexed to Munster, on petition of the Earl of Thomond.

With the exception of three parishes in the diocese of Limerick, Clare is included in the dioceses of Killaloe and Kilfenora, the whole of the latter one being comprised within its limits : the county is wholly in the province of Dublin. For purposes of civil jurisdiction it is divided into the baronies of Bunratty Upper, Bunratty Lower. Burren, Clonderlaw, Corcomroe, Ibrickane, Inchiquin, Islands, Moyarta, Tulla. or Tullagh Upper, and Tulla or Tullagh Lower. It contains the borough and market-town of Ennis ; the sea-port and market-town of Kilrush ; the market and post towns of Curofin and Ennistymon ; the post towns or villages of Newmarket-on-Fergus, Six-mile-Bridge, Scariff, Killaloe, Kildysert, Miltown-Malbay, Knock, Broadford, New Quay, and Bunratty ; the town and port of Clare ; and the smaller towns of Kilkee and Liscanor, the latter of which has a harbour. The election of the two members returned by this county to the Imperial parliament, takes place at Ennis : the constituency registered in 1843 amounted to 2015, whereof 324 were £50, 148 £20, and 1385 £10, freeholders ; 14 £20, and 126 £10, leaseholders ; and 18 rent-chargers. There never was more than one parliamentary borough, that of Ennis, which sent two members to the Irish parliament, and still sends one to that of the United Kingdom. Clare is included in the Munster circuit : the assizes are held at Ennis, and the quarter-sessions at Ennis, Six-mile-Bridge, Kilrush, Ennistymon, and Miltown-Malbay. The county gaol is at Ennis, and there are bridewells at Kilrush, Tulla, Six-mile-Bridge, and Ennistymon : the number of persons charged with criminal offences, and committed to the county gaol in 1844, was 621. The local government is vested in a lieutenant, 17 deputy-lieutenants, and 113 other magistrates, with the usual county officers, including three coroners. The number of constabulary police stations is 54, having in the whole a force consisting of a county inspector, 8 sub-inspectors, 7 head constables, 44 constables, and 249 sub-constables, with 9 horses; maintained equally by grand jury presentments and by government. Parties of the revenue police are stationed at Ennis and Killaloe. At Ennis are the county house of industry, the county infirmary, and a fever hospital ; besides which there are 24 dispensaries, situated respectively at Curofin, Doonass, Ballyvanghan, Six-mile-Bridge, Carrigaholt, Kilrush, Ennistymon, Tomgrany, Kildysert, Newmarket, Killaloe, &e., and all maintained by grand jury presentments and voluntary contributions in equal portions. The total amount of grand jury presentments, for 1844, was £41,913. In military arrangements this county is included in the Limerick district : it contains the three barrack stations of Clare Castle, Killaloe, and Kilrush, affording in the whole accommodation for 19 officers and 325 men; and there are small parties stationed at the respective forts or batteries of Kilkerin, Scattery Island, Dunaha, and Kileredane, erected during the continental war to protect the trade of Limerick, and each affording barrack accommodation to 16 artillerymen; also at Aughnish Point sad Finvarra Point, on the southern shore of the bay of Galway.

The county possesses every diversity of surface and great natural advantages, which require only the hand of improvement to heighten into beauty. Of the barony of Tulla, forming its entire eastern part, the northern portion is mountainous and moory, though capable of improvement ; the eastern and southern portions are intersected by a range of lofty hills, and studded with numerous demesnes in a high state of cultivation. There is a chain of lakes, also extending through this and the adjoining barony of Bunratty, which might easily be converted into a direct navigable line of communication between Broadford, Six-mile-Bridge, and the river Shannon. Bunratty barony, which includes the tract between this and the river Fergus, has in the north a large proportion of rocky ground, which is nevertheless tolerably productive, very luxuriant herbage springing up among the rocks, and affording pasturage for flocks of sheep. The southern portion of this harony, adjoining the rivers Fergus and Shannon, contains some of the richest land in the county, both for tillage and pasturage ; the uplands of this district are also of a superior quality. Inchiquin barony, lying to the north-west of Bunratty, has in its eastern part chiefly a level surface, with a calcareous, rocky, and light soil ; the western consists mostly of moory hills, with some valleys of great fertility. The part adjoining the barony of Corcomroe is highly improvable, limestone being every where obtained. The barony of Islands, which joins Inchiquin on the south and Bunratty on the west, is chiefly composed, on the western side, of low moor), mountain ; but towards the east, approaching the town of Ennis and the river Fergus it greatly Improves, partaking of the same qualities of soil as Bunratty, and containing a portion of the corcasses.. Between Islands and the Shannon is the barony of Clonderlaw, very much encumbered with bog and moory mountain, but highly improvable, from the facility of obtaining lime and sea manure. The four remaining baronies stretch along the western coast. That of Moyarty constitutes the long peninsula between the Shannon and the Atlantic, forming the south-western extremity of the county, and terminating at Cape Lean or Loop Head, where there is a lighthouse: this barony also abounds with bog and moory hills, capable of great improvement. The southern part of Ibrickane, which lies north of Moyarty, is nearly all bog, and the northern is composed of a mixture of improvable moory hills and a clay soil. Corcomroe, the next maritime barony on the north, is of the same character as the last mentioned lands, having a fertile clay soil on whinstone rock, here called coId-stone, to distinguish it from limestone the land about Kilfenora and Doolan is some of the richest in the county. Burren, forming the northern extremity of the county, is very rocky, but produces a short, sweet herbage excellently adapted for sheep of middle size and short clothing wool, of which immense numbers are raised upon it, together with some store cattle. Besides the numerous picturesque islands in the Shannon and Fergus rivers, there are various small islets on the coast, in the bay of Galway, and in the great recess extending from Dunbeg to Liscanor, called Malbay, an iron-bound coast rendered exceedingly dangerous by the prevalence of westerly winds. The principal of these is Mutton Island, near which are Goat Island and Enniskerry Island, the three forming a group of the latter name. The coast at Moher presents a magnificent range of precipitous cliffs, varying from 600 to nearly 1000 feet in height above the sea at low water, and on the summit of which a banqueting-house in the castellated style was lately erected by Cornelius O’Brien, Esq., for the use of the public. The lakes are very numerous, upwards of 100 having names : the majority are small, though some are of large extent, namely, Lough Graney, Lough O’Grady, Lough Tedane, and Lough Inchiquin ; the last is remarkable for its picturesque beauty and for its fine trout. Turloughs, called in other places Loghans, are frequent; they are tracts either of water forced under ground from a higher level, or of surface water collected on low grounds, where it has no outlet, and remains until evaporated in summer. There is a very large one at Turloghmore ; two may be seen near Kilfenora, and more in other places. Although the water usually remains on the surface for several months, yet on its subsiding, a fine grass springs up, that supports great numbers of cattle and sheep.

The climate is cool, humid, and occasionally subject to boisterous winds, but remarkably conducive to health . frost or snow are seldom of long continuance. So powerful are the gales from the Atlantic, that trees upwards of fifty miles from the shore, if not sheltered, incline to the east. On the rocky parts of the coast these gales cause the sea, by its incessant attrition, to gain on the land . but where sand forms the barrier, the land is increasing. The SOIL of the mountainous district extending from Doolan southward towards Loop Head, and thence along the Shannon to Kilrush, and even still further in the same direction, together with that of the mountains of Slieveboghta, which separate the county from Galway, is generally composed of moor or bog of different depths, from two inches to many feet, over a ferruginous or aluminous clay, or sandstone rock. It is highly capable of improvement by the application of lime, which may be procured either by land carriage or by the Shannon. A large portion of the level districts is also occupied by bogs, particularly in the baronies of Moyarty and Ibrickane, where there is a tract of this character extending from Kilrush towards Dunbeg, about five miles in length, and of nearly equal breadth. On the boundaries of the calcareous and schistose regions the soils gradually intermingle, and form some of the best land in the county, as at Lemenagh, Shally, Applevale, Riverstown, &c. A piece of ground of remarkable fertility also extends from Kilnoe to Tomgraney, for about a mile in breadth. But the best soil is that of the rich low grounds called corcasses, which extend along the rivers Shannon and Fergus, from a place named Paradise to Limerick, a distance of more than 20 miles. They are computed to contain upwards of 20,000 acres, and are of various breadth, indenting the adjacent country in a great diversity of form. From 18 to 20 crops have been taken successively from them without any application of manure; they are adapted to the fattening of the largest oxen, and furnish vast numbers of cattle to the merchants of Cork and Limerick for exportation. The part called Tradree, or Tradruihe, is proverbially rich. These corcasses are called black, or blue, according to the nature of the substratum : the black is the more valuable for tillage, as it does not retain the wet so long as the blue, which latter consists of a tenacious clay. The soil in the neighbourhood of Quinn Abbey is a light limestone, and there is a large tract of fine arable country where the parishes of Quinn, Clonlea, and Kilmurry-Negaul unite.

The arable parts of the county produce abundant crops of potatoes, oats, wheat, barley, flax, &c. A large portion of the tillage is executed with the spade, especially on the sides of the mountains and on rocky ground, partly owing to the unevenness of the surface and partly to the poverty of the cultivators. The system of cropping too often adopted is the impoverishing mode of first burning or manuring for potatoes, set two or three years successively ; then taking one crop of wheat, and lastly repeated crops of oats, until the soil is completely exhausted. But this system is gradually giving place to a better. Fallowing is practised to some little extent ; and many farms are cultivated on an improved plan, one important part of which is an alternation of green crops. A superior method of spade husbandry (trenching or Scotch drilling) has been introduced, and if generally adopted would be productive of great advantages. Vast quantities of potatoes, usually boiled, and sometimes mixed with bran, are used to feed cows and other cattle in winter. Beans were formerly sown to a great extent in the rich lands near the rivers Shannon and Fergus, but this practice has greatly declined. Red clover and rye-grass are the only artificial grasses generally sown. The corcasses yield six tons of hay per Irish acre, and even eight tons are sometimes obtained. Except near the town of Ennis, there was till lately but a very small number of regular dairies, a few farmers and cottagers merely supplying the neighbouring villages with milk and butter. A considerable quantity of butter is sent to Limerick from Ennis, being chiefly the produce of the pastures near Clare and Barntick ; and it is also now made by the small farmers in most parts, and sent to Limerick for exportation to London.

The pastures of Clare are of sufficient variety for rearing and fattening stock of every kind. Much diversity is presented by the limestone crags of Burren, and the eastern part of the baronies of Corcomroe and Inchiquin, which are, with few exceptions, devoted to the pasturage of young cattle and sheep, though in some places so rugged that four acres would not support one of the latter. Intermixed with the rocks, are found lands of a good fattening quality, producing mutton of the finest flavour, arising from the sweetness of the herbage ; though to a stranger it might appear that a sheep could scarcely exist upon them. The parishes of Kilmoon and Killeiny, in Burren, contain some of the best fattening land in the county. Large tracts of the mountains are let by the bulk, and not by the acre. The other baronies of the county likewise present every variety, from the rich corcass to mountains producing scarcely any thing but heath and carex of various sorts, barely sufficient for keeping young cattle alive. The inclosed pastures are often of very inferior quality, from the ground having been exhausted with corn crops, and never laid down with grass seeds, but allowed to recover its native herbage; a gradual improvement, however, is taking place in this respect. But the great defect consists in not properly clearing the ground. In the eastern and western extremities of the county, the pasture land is usually reclaimed mountain or bog, having a coarse sour herbage, intermixed with carex, and capable of sustaining only a small number of young cattle. The herbage between Poulanishery and Carrigaholt is remarkable for producing good milk and butter. That of the sand hills opposite Liscanor bay and along the shore from Miltown to Dunbeg, is also of a peculiar kind : these elevations consist entirely of sands blown in by the westerly winds, and accumulated into immense hills by the growth of various plants,, the first of which was perhaps sea-reed or mat-weed.

Besides the home manures, some farmers apply (though not to a sufficient extent) limestone-gravel, which is found in different parts . limestone, now used very extensively ; marl, of which the bed of the Shannon produces inexhaustible quantities, and by the use of which astonishing improvements have been effected in the neighbourhood of Killaloe , and other species of marl, of less fertilizing powers, dug at Kilnoe, and between Feacle and Lough Graney, in the barony of Tulla. Near the coast are obtained sea-sand and sea- weed, with which the potato-ground is plentifully manured, and which are frequently brought up the Fergus by boats to Ennis, and thence into the country, a distance of four miles. Ashes, procured by burning the surface of the land, until lately formed a very large portion of the manure used here ; but the employment of them is now much condemned, especially for light soils. Great improvements have been made upon the old rude implements of agriculture ; the Scotch plough is generally used. In the rocky regions the only fences are, of necessity, stone walls, mostly built without mortar: walls ten feet thick, made by clearing the land of stones, are not uncommon in these districts. The Cattle are nearly all long horned, generally well-shaped about the head, and tolerably fine in the limb, good milkers, and thrifty. A few of the old native breed are still found, chiefly in mountainous situations : they are usually black or of a rusty brown, have black turned horns and large bodies, and are also good milkers and very hardy. The improved Leicester breed has been introduced to a great extent, and of late years the short-horned Durham and Ayrshire cattle have been in request. Oxen are not often used in the labours of husbandry. The short and fine staple of the wool of the native Sheep has been much deteriorated by the introduction of the Leicester breed, but the encouragement of the South Down may in a measure restore it. The breed of Swine has been highly improved, the small short-eared pig being now universal. The breed of Horses has also undergone improvement ; the horse-fair of Spancel Hill is attended by dealers from all parts of Ireland. The chief markets for the fat-cattle are Cork and Limerick ; great numbers of heifers are sent to the fair of Ballinasloe. Formerly there were extensive orchards in this county, especially near Six-mile-Bridge ; and a few still remain. Very fine cider is made from apples of various kinds, mixed in the press, and it is in such repute that it is generally bought for the consumption of private families, principally resident.

Few counties present a greater deficiency of wood, though few afford more favourable situations for the growth of timber where sheltered from the cold winds of the Atlantic : the practice of planting is gaining ground, but the general surface of the county is still comparatively bare. The most valuable timber is that found in the bogs ; it consists of fir, oak, and yew, but chiefly the two former : in red bogs, fir is usually found ; in black bogs, oak. The fir is frequently of very large dimensions, and most of the farmers’ houses near places where it can be procured are roofed with it. The manner of finding these trees is somewhat curious : very early in the morning, before the dew evaporates, a man takes with him to the bog a long, slender, sharp spear, and as the dew never lies on the part over the trees, he can ascertain their situation and length, and, thrusting down his spear, can easily discover whether they are sound or decayed ; if sound, he marks with a spade the spot where they lie, and at his leisure proceeds to extricate them from their bed. Along the coast of Malbay, where not even a furze-bush will now grow, large bog trees are often found. The extensive boggy wastes are susceptible of great improvement : the only part not containing large tracts of this kind is the barony of Burren, the inhabitants of the maritime parts of which bring turf in boats from the opposite coast of Connemara. On the other hand, a considerable quantity of turf is carried from Poulanishery to Limerick bay, a water carriage of upwards of forty miles ; for the supply of which trade, immense ricks are always ready on the shore ; and sometimes the boats return laden with limestone from Askeaton and Aughnish. Although many tracts formerly waste, including all the corcasses, have been gained from the Fergus and the Shannon, yet a large portion of the marshes on their banks still remains subject to the overflow of these rivers. The fuel chiefly used is turf, but a considerable quantity of coal is now consumed by respectable families.

The principal minerals are, lead, iron, manganese, coal, slate, limestone, and various kinds of building-stone. Very rich Lead-ore has been found near Glendree, near Tulla, at Lemenagh, and at Glenvaan in the barony of Burren : a vein of lead was discovered, in 1834, at Ballylicky near Quinn, the ore of which is of superior quality, and very productive ; it is shipped at Clare, for Wales. There are strong indications of Iron in many parts, especially near the western coast ; but it cannot be rendered available until a sufficient vein of coal shall have been found in its vicinity, Manganese occurs at Kilcredane Point near Carrigaholt Castle, near Newhall, on the edge of a bog near Ennistymon, and at the spa-well of Fierd on the sea-shore, near Cross, where it is formed by the water on the rocks. Coal has been found in many places, particularly near the coast of the Atlantic ; but few efforts have been made to pursue the search with a view to work it. The best Slates are those of Broadford and Killaloe, the former of which have long been celebrated, though the latter are superior ; both are nearly equal to the finest Welsh slates : the Killaloe quarry is worked to a greater depth than the quarries of Broadford. Near Ennistymon are raised thin flags, used for many miles around for covering houses, but requiring strong timbers to support them. The Ballagh slates are however preferred for roofing, as being thinner than most of the same kind. There is another quarry of almost the same sort near Kilrush ; also one near Glenomera, and others in the western part of the county. At Money Point, on the Shannon, a few miles from Kilrush, are raised very fine flags, which are easily quarried in large masses. Limestone occupies all the central and northern parts of the county, in a vast tract bounded on the south by the Shannon, on the east by a line running parallel with the Ougarnee river to Scariff bay, on the north by the mountains in the north of Tulla and the confines of Galway, and on the west by Galway bay and a line including Kilfenora, Curofin, and Ennis, and meeting the Shannon at the mouth of the Fergus. The limestone rises above the surface in Burren and in the eastern parts of Corcomroe and Inchiquin, in some places exhibiting a smooth and unbroken plane of several square yards ; the calcareous hills extending in a chain from Curofin present a very curious aspect, being generally isolated, flat on the summit, and descending to the intervening valleys by successive ledges. Detached limestone rocks of considerable magnitude frequently occur in the grit soils ; and large blocks have been discovered in Liscanor bay, seven or eight miles from the limestone district: in a bank near the harbour of Liscanor, water- worn pebbles of limestone are found and burned. At Craggleith, near Ennis, a fine black Marble, susceptible of a very high polish, is procured. The shores of Lough Graney, in the north-eastern extremity of the county, produce a Sand chiefly composed of crystals, which is sought for by the country people for upwards of 20 miles around, and is used for scythe boards, which are much superior to those brought from England : sand of similar quality is likewise procured from Lough Coutra, in the same mountains. Copper pyrites occur in several parts of Burren. An unsuccessful attempt to raise copper-ore has been made at Glenvaan. In the time of James I., as appears from a manuscript in the Harleian collection, there was a Silver-mine adjacent to O’Loughlin’s Castle in Burren ; and an old interpolator of Nennius mentions that precious metals abounded here. Antimony, valuable ochres, clays for potteries, and beautiful fluor-spar, have likewise been discovered in small quantities.

Linen, generally of coarse quality, is manufactured by the inhabitants in their own dwellings, for home consumption. A small quantity of coarse diaper for towels is also made, and generally sold at the fairs and markets, as is canvas for sacks and bags ; but this trade is now very limited. Frieze is made, chiefly for home use ; and at Curofin and Ennistymon, coarse woollen stockings, the manufacture of the adjacent country, are sold every market-day , they are not so fine as the stockings made in Connemara, but are much stronger. The only mills besides those for corn are a few tuck- mills scattered over the country. Yet there is no lack of water-power : the river Ougarnee, from its copiousness and rapidity, is well adapted for supplying manufactories of any extent, and runs through a populous country.

Though the numerous bays and creeks on the Shannon, from Loop Head to Kilrush, are excellently adapted for the fitting out and harbourage of fishing boats, the business is pursued with little spirit. The boats that are used are not considered safe to be rowed within five miles of the mouth of the Shannon, and from their small size, the fish caught is not more than sufficient for supplying the markets of Limerick, Kilrush, and Miltown, and the southern aud western parts of the county ; the northern and eastern being chiefly supplied from Galway. In the herring season, from 100 to 200 boats are fitted out in this river for the fishery, which, however, is very uncertain. It is thought that a productive turbot-fishery might be carried on in the mouth of the river, but there are no vessels or tackling adapted for it. The boats are chiefly such as have been used from the remotest ages, being made of wicker-work, and formerly covered with horse or cow hides, but latterly with canvas ; they are generally about 30 feet long, and only three broad, and are well adapted to encounter the surf, above which they rise on every wave. Kilrush has some larger boats. In Liscanor bay, a considerable quantity of small turbot is occasionally caught. Fine mullet and bass are sometimes caught at the mouths of the rivers; and many kinds of flat-fish, together with mackerel and whiting, are taken in abundance in their respective seasons. Oysters are procured on many parts of the coast. Those at Pouldoody, on the coast of Burren, have long been in high repute for their fine flavour : the bed, however, is of small extent, and the property of a private gentleman, and the fish are not publicly sold. Near Pouldoody is the great Burren oyster-bed, called the Red Bank, where a large establishment is maintained, and from which a constant supply is furnished for the Dublin and other markets. Oysters are also taken at Scattery Island, and on the shores of the Shannon, particularly at Querin and Poulanishery; the beds are small but the oysters good, and almost the whole of their produce is sent to Limerick. Crabs and lobsters are caught in abundance on the shores of the bay of Galway, in every creek from Black Head to Ardfry; and are also procured, in smaller quantities, on the coast of the Atlantic, from Black Head to Loop Head. The salmon-fishery of the Shannon is very considerable, and a few are taken in every other river. Eels are abundant, and weirs for taking them are extremely numerous. The commerce of the county consists entirely in the exportation of agricultural produce, and the importation of various foreign articles for home consumption s of this trade Limerick is the centre, although Kilrush likewise participates in it. The only harbours between the mouth of the Shannon and Galway bay, an extent of upwards of 40 miles, are, Dunmore, which is rendered dangerous by the rocks at its entrance; and Liscanor, which is capable of properly sheltering only fishing-boats. The fine river Fergus is made but little available for the purposes of commerce, the trade with Limerick being chiefly by an expensive land carriage. The corn-markets are those of Ennis, Clare, and Kilrush, which are very abundantly supplied, and much grain is purchased at them for the Limerick exporters; corn is also shipped for Galway at Ballyvaughan and New Quay, on the north coast.

The most important river is the Shannon, which first touches the county on its eastern confines as part of Lough Derg, and thence sweeps round by Killaloe, where it forms the celebrated falls and separates the county from the county of Tipperary. Passing thence to O’Brien’s-Bridge, along the boundary of the county of Limerick, it flows on to Limerick, from which city to the sea, a distance of 60 miles, it forms a magnificent estuary, nine miles wide at its mouth, between Kerry Head in the county of Kerry, and Loop Head in that of Clare, where it opens into the Atlantic. This noble river is diversified by many picturesque islands, bays, and promontories It washes no less than 97 British miles of the boundary of Clare , is the great channel of the trade of the county ; and, besides its maritime advantages, affords a navigable access to all the central parts of the kingdom, and to Dublin. The navigation, however, was incomplete until, through the exertions of the Board of Inland Navigation, the obstacles at Killaloe were avoided by the construction of an artificial line for some distance. The numerous bays and creeks on both its sides render it, in every wind, perfectly safe to the vessels navigating to Limerick, the quays of which place are accessible to ships of large burthen. The Fergut, a river of this county exclusively, has its source in the parish of Clonney, barony of Corcomroe, and running through the lakes of Inchiquin, Tedane, Dromore, Ballyally, and several others, and receiving the waters of various smaller streams, pursues a southern course to the town of Ennis, where it is augmented by the waters of the Clareen. Flowing thence, by Clare, it spreads below the latter place into a wide and beautiful estuary, studded with picturesque islands and opening into the Shannon : from this river it is navigable up to Clare, a distance of eight miles, for vessels of nearly 500 tons’ burthen; and up to Ennis for small craft. Its banks in many places present a rich muddy strand, capable of being inclosed so as to form an important addition to the corcass lands : it receives many mountain streams, and after heavy rains rises so rapidly, that large tracts of low meadow are occasionally overflowed, and the hay destroyed. The Scariff rises in Lough Ferroig on the top of the mountain of Slieveboghta, in the barony of Tulla, and on the confines of Galway, and runs southward into he beautiful Lough Graney : winding hence eastward it collects the superfluous waters of Annalow Lough and Lough O’Grady, and, about two miles below the latter, fulls into Scariff bay, a picturesque part of Lough Derg. The fine stream of Ougarnee rises near and flows through Lough Breedy, communicates with Lough Doon, receives the waters of Lough Clonlea, and, after forming of itself a small lake near Mountcashel, in the parish of Kilfinaghty, pursues its southern course by Six-mile-Bridge, and falls into the Shannon near Bunratty Castle, about nine miles below Limerick ; the tide flows nearly to Six-mile-Bridge. The other considerable streams are the Ardsallas, Blackwater, and Clareen, and the Ennistymon river: the smaller streams are almost innumerable, except in the barony of Burren, which is scantily supplied.

Except the canal between Limerick and Killaloe, there is no artificial line of navigation, although it has been proposed to construct a canal from Poulanishery harbour, about twelve miles distant from Loop Head, across the peninsula to Dunbeg, and another from the Shannon, at Scariff bay, through Lough Graney, to Galway bay. The roads are numerous, and generally in good repair : the principal have been much improved within the last few years, and many hills have been lowered. Soon after the famine and distress of 1822, a new road was made near the coast, between Liscanor, Miltown-Malbay, and Kilrush, and another between the last-named place and Ennis. The roads recently completed, and in aid of which grants were made by the Board of Public Works, are, a direct road leading from the newly-erected Wellesley-bridge at Limerick to Cratloe, partly at the expense of the Marquess of Lansdowne; a road from Knockbreda to the boundary of the county towards Loughrea, extending along the eastern side of Lough Graney, and proposed to be continued to Kiltannan, towards Tulla and Ennis , and a road along the shore of Lough Derg, between Killaloe and Scariff. A road has also been made, at the expense of the county, from Scariff bay, along the northern side of Lough O’Grady and the western side of Lough Graney, to the boundary of the county, towards Gort ; with a branch to the south, towards O’Callaghan’s Mills. The bridges are generally good : a handsome new bridge has been built, under the superintendence of the Board of Public Works, over the Fergus at Ennis; and another, of large dimensions and elegant structure, over the Inagh near Liscanor.

The remains of antiquity are numerous and diversified. There are cromlechs at Ballygannor, Lemenagh, Kilnaboy, Tullynaglashin, Mount Callan, and Ballykishen ; near the last-named are two smaller, and the remains of a cairn. Raths abound in every part, and many have been planted with fir-trees; one occupies the spot near Killaloe where formerly stood King Brien Boroihme’s palace, or castle, called Kinkora. Pillar-stones occur only in a few places , some may be seen on the road between Spancel Hill and Tulla. Of the ancient round towers, this county contains five, viz., those of Scattery Island, Drumcleeve, Dysert, Kilnaboy, and Inniscalthra, in Lough Derg. Near the cathedral of Killaloe is the oratory of St. Moluah, supposed to be one of the oldest buildings in Ireland. Thirty religious houses were founded in this county, but at present there are remains only of those of Corcomroe, Ennis, Quiun, Inniscalthra, and Inniscattery. At Kilfenora, several ancient crosses of great curiosity are to be seen ; a very remarkable one is fixed on a rock near the church of Kilnaboy ; and near the church and round tower of Dysert a very curious one lies on the ground. The castles still existing entire or in ruins amount in number to 120, of which the family of Mac Namara, it is traditionally said, built 57. There are 25 in the barony of Bunratty, of which those of Bunratty and Knopoge are inhabited ; 13 in Burren, of which those of Castletown and Glaninagh are inhabited, and New-town Castle is a round fortress on a square base ; 8 in Clonderlaw, of which that of Donogrogue is inhabited; 14 in Corcomroe, of which that of Smithstown is inhabited ; 6 in Ibrickane ; 22 in Inchiquin, of which those of Mahre and Dysert are inhabited ; 3 in Islands , 4 in Moyarta, of which that of Carrigaholt is inhabited ; and 25 in Tulla. Many of them are insignificant places, built by the proprietors in times of lawless turbulence ; others, small castellated houses erected by English settlers. Bunratty Castle, however, is of considerable extent, and was once considered a place of great strength.

The better class of farmers and graziers have generally comfortable dwelling-houses and convenient offices, with roofs of slate or flags. The poorer classes are usually badly lodged in houses built of stone without mortar, and the walls of which are consequently pervious to the wind and rain. The cottages are always thatched, either with straw, sedges, rushes, heath, or potato-stalks : a want of cleanliness is universally prevalent. Few cottages are without sallow-trees, for kishes or baskets, which many of the labourers know how to make ; and almost all have small potato-gardens. The Irish yet spoken in the remote parts of the county is chiefly a jargon of Irish with English intermixed, and is rapidly falling into disuse. Hurling matches are a favourite sport of the peasantry; and chairs, or meetings of both sexes at night in some public-house, constitute another source of amusement Mineral Waters are found in many places, chiefly chalybeate : that at Lisdounvarna has long been celebrated for its efficacy in visceral complaints ; at Scool and Kilkishen are others well known ; and two more are situated near Cloneen, about a mile north-west of Lemenagh Castle, and at Cassino near Miltown-Malbay. Many holy wells, remarkable naturally only for the purity of their waters, exist in different parts, but are little regarded except by the peasantry. The great falls in the Shannon, near Killaloe, are worthy of especial notice. The title of Earl of Thomond, derived from this county, was raised to a Marquesate in 1800, in favour of the family of O’Brien, which also derives from the extensive territory of Inchiquin the titles of Earl and Baron, and from the district of Barren that of Baron. The title of Earl of Clare is borne by the family of Fitzgibbon.

Leave a reply