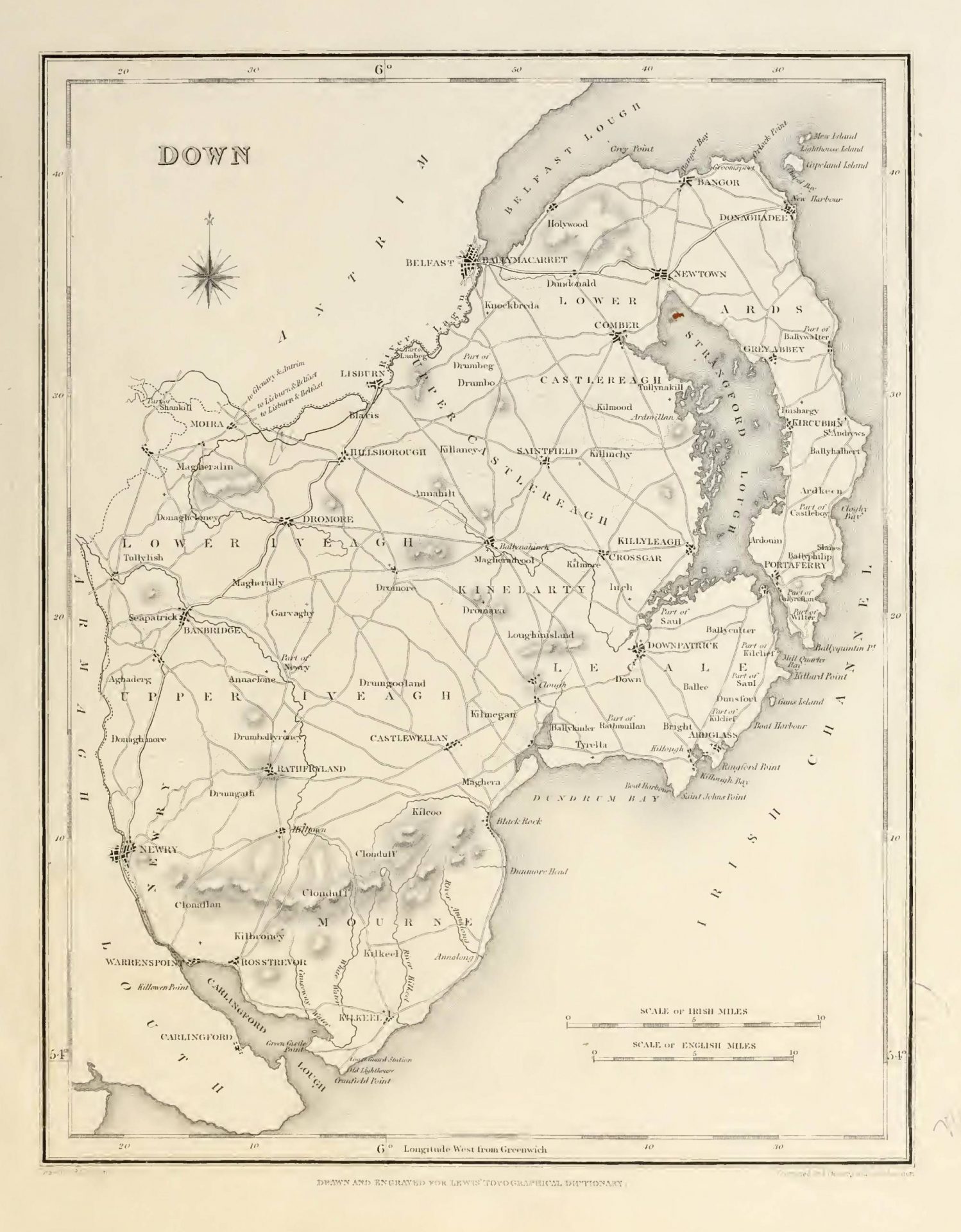

DOWN (County of), a maritime county of the province of Ulster, bounded on the east and south by the Irish Sea, on the north by the county of Antrim and Carrickfergus bay, and on the west by the county of Armagh. It extends from 54° 0′ to 54° 40′ (N. Lat.) and from 5° 18′ to 6° 20′ (W. Lon.); and comprises an area of 612,495 statute acres, of which 514,180 are arable, 78,317 uncultivated, 14,355 plantations, 2211 under towns and villages, and 3432 under water. The population, in 1821, amounted to 325,410; in 1831, to 352,012; and in 1841, to 361,446.

This county, together with a small part of that of Antrim, was anciently known by the name of Ulagh or Utlagh, in Latin Ulida, said by some to be derived from a Norwegian of that name who flourished here long before the Christian era. The appellation was finally extended to the whole province of Ulster. Ptolemy, the geographer, mentions the Voluntii or Uluntii as inhabiting this region; and the name, by some etymologists, is traced from them. At what period this tribe settled in Ireland is unknown: the name is not found in any other author who treats the country; whence it may be inferred that the colony was soon incorporated with the natives, the principal families of whom were the O’Nials, the Mac Gennises, the Macartanes, the Slut-Kellys, and the Mac Gilmores. The county was chiefly in the possession of the same families at the period of the settlement of the north of Ireland in the reign of King James, at the commencement of the seventeenth century, with the addition of the English families of Savage and White, the former of which had settled in the peninsula of the Ardes, on the eastern side of Strangford lough, and the latter in the barony of Dufferin, on the western side of the same gulf. It is not clearly ascertained at what precise period the county was made shire ground. The common opinion is, that this arrangement, together with the division into baronies, occurred in the early part of the reign of Elizabeth. But from the ancient records of the country, it appears that, previously to the 20th of Edward II., here were two counties distinguished by the names of Down and Newtown. The barony of Ardes was also a separate jurisdiction, having sheriffs of its own, at the same date; and the barony of Lecale was considered to be within the English pale from its first subjugation by that people, its communication with the metropolis being maintained chiefly by sea, as the Irish were in possession of the mountain passes between it and Louth. That the consolidation of these separate jurisdictions into one county took place previously to the settlement of Ulster by Sir John Perrott during his government, which commenced in 1584, is evident from this settlement comprehending seven counties only, omitting those of Down and Antrim because they had previously been subjected to the English law.

The first settlement of the English in this part of Ulster took place in 1177, when John de Courcy, one of the British adventurers who accompanied Strongbow, marched from Dublin with 22 men-at-arms and 300 soldiers, and arrived at Downpatrick in four days, without meeting an enemy. But when there he was immediately besieged by Dunleve, the toparch of the country, aided by several of the neighbouring chieftains, at the head of 10,000 men. De Courcy, however, did not suffer himself to be blockaded, but sallied out at the head of his little troop, and routed the besiegers. Another army of the Ulidians having been soon after defeated with much slaughter in a great battle, he became undisputed master of the part of the county in the vicinity of Downpatrick, which town he made his chief residence, founding several religious establishments in its neighbourhood. In 1200 Roderic Mac Dunleve, toparch of the country, was treacherously killed by De Courcy’s servants, who were banished for the act by his order; in 1203 De Courcy himself was seized (while doing penance unarmed in the burial-ground of the cathedral of Down) by order of De Lacy, the chief governor of Ireland, and was sent prisoner to King John in England. The territory then came into the possession of the family of De Lacy, by an heiress of which, about the middle of the same century, it was conveyed in marriage to Walter de Burgo. In 1315, Edward Brute having landed in the northern part of Ulster, to assert his claim to the throne of Ireland, this part of the province suffered severely in consequence of the military movements attending his progress southwards and his return. Some years after, William de Burgo, the representative of that powerful family, having been killed by his own servants at Carrickfergus, and leaving an only daughter, the title and possessions were transferred by marriage to Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, through whom they became vested in the kings of England.

Downshire is partly in the diocese of Down, and partly in that of Dromore, with a small portion in that of Connor. For purposes of civil jurisdiction, it is divided into the baronies of Ardes, Castlereagh, Dufferin, Iveagh Lower, Iveagh Upper, Kinelarty, Locale, and Mourne, and the extra-episcopal lordship of Newry. It contains the borough, market, and assize town of Down-patrick; the greater part of the borough, market, and assize town, and sea-port, of Newry; the ancient corporate, market, and post towns of Bangor, Newtown-Ardes, Hillsborough, and Killyleagh; the sea-port, market and post towns of Portaferry and Donaghadee; the market and post towns of Banbridge, Saintfield, Kirkcubbin, Rathfriland, Castlewellan, Ballinahinch, and Dromore; the sea-port and post towns of Strangford, Warrenpoint, Rostrevor, Ardglass, and Killough; the sea-port of Newcastle, which has a sub-post; the post-towns of Clough, Comber, Dromaragh, Hollywood, Moira, Loughbrickland, Kilkeel, and Gilford; and a suburb of the town of Belfast, called Ballymacarret. Prior to the Union it sent fourteen members to the Irish parliament; namely, two for the county at large, and two for each of the boroughs of Newry, Downpatrick, Bangor, Hillsborough, Killyleagh, and Newtown-Ardes. It is at present represented by four members, namely, two for the county, and one for each of the boroughs of Newry and Downpatrick. The number of county voters registered in 1843 was 2243, of whom 316 were £50, 176 £20, and 1654 £10, freeholders; 15 £20, and 225 £10, leaseholders; and eight rent-chargers. The election takes place at Downpatrick. Down is included in the north-east circuit: the assizes are held at Downpatrick, where are the county gaol and court-house; quarter-sessions are held at Newtown-Ardes, Hillsborough, Downpatrick, and Newry. The local government is vested in a lord-lieutenant, 28 deputy lieutenants, and 145 other magistrates, besides whom there are the usual county officers, including two coroners. There are 39 constabulary police stations, having in the whole a force of a county inspector, 6 sub-inspectors, 7 head-constables, 26 constables, and 139 sub-constables, with 7 horses; the expense of whose maintenance in 1842 was £9433, defrayed equally by grand jury presentments and by government. There are a county infirmary and a fever hospital at Down-patrick; and dispensaries situated respectively at Banbridge, Kilkeel, Rathfriland, Castlewellan, Dromore, Warrenpoint, Donaghadee, Newry, Newtownbreda, Hollywood, Hillsborough, Ardglass, and Bangor, maintained equally by private subscriptions and grand jury presentments. In the military arrangements Down is included in the Belfast district, and contains two barrack stations for infantry, one at Newry and one at Downpatrick. On the coast are nineteen coast-guard stations, under the command of two inspecting commanders, in the districts of Donaghadee and Newcastle, with a force of 15 chief officers and 127 men.

The county has a pleasing inequality of surface, and exhibits a variety of beautiful landscapes. The mountainous district is in the south, comprehending all the barony of Morne, the lordship of Newry, and a considerable portion of the barony of Iveagh: the mountains rise gradually to a great elevation, terminating in the towering peak of Slieve Donard; and to the north of this main assemblage is the detached group of Slieve Croob, the summit of which is 964 feet high. There are several lakes, but none of much extent: the principal is, Aghry or Agher, and Erne, in Lower Iveagh; Ballyroney, Loughbrickland, and Shark, in Upper Iveagh; Ballinahinch, in Kinelarty, and Ballydugan, in Lecale. The county touches upon Lough Neagh in a very small portion of its north-western extremity, near the place where the Lagan canal discharges itself into the lake. Its eastern boundary, including also a portion of the northern and southern limits, comprehends a long line of COAST, commencing at Belfast with the mouth of the Lagan, which separates this county from that of Antrim, and proceeding thence along the southern side of Carrickfergus bay. Here the shore rises in a gentle acclivity, richly studded with villas, to the Castlereagh hills, which form the back ground. Off Orlock Point, at the southern extremity of the bay, are the Copeland Islands, to the sooth of which is the harbour of Donaghadee, a station for the mail-packets between Ireland and Scotland. On the coast of the Ardes are, Ballyhalbert bay, Cloughy bay, and Quintin bay, with the islets called Burr or Burial Island, Green Island, and Bard Island. South of Quintin bay is the channel, about a mile wide, to Strangford lough, called also Lough Cone. The lough itself is a deep gulf stretching ten miles into the land in a northern direction, to Newtown-Ardes, and having a south-western offset, by which vessels of small burthen can come within a mile of Downpatrick. The interior is studded with numerous islands, of which Boate says there are 260: Harris counts 54 with names, besides many smaller; a few are inhabited, but the others are mostly used for pasturage, and some are wooded. South of Strangford lough are Gun’s Island, Ardglass harbour, and Killough bay. Dundrum bay, to the south-west, forms an extended indentation on the coast, commencing at St. John’s Point, south of Killough, and terminating at Cranfield Point, the southern extremity of the county, where the coast takes a north-western direction by Greencastle, Rostrevor, and Warrenpoint, forming the northern side of the romantic and much-frequented bay of Carlingford.

The extent and varied surface of the county necessarily occasion a great diversity of soil: indeed, there exists every gradation from a light sandy loam to a strong clay; but the predominant soil is a loam, not of great depth, but good in quality, though in roost places intermixed with a quantity of stones of every size. When clay is the substratum of this loam, it is retentive of water, and more difficult to improve, but on being thoroughly cultivated, its produce is considerable and of superior quality. As the subsoil approaches to a hungry gravel, the loam diminishes in fertility. Clay is mostly confined to the eastern coast of the Ardes and the northern portion of Castlereagh, in which the soil is strong and of good quality. Of sandy ground, the quantity is still less, being limited to a few stripes scattered along the shores, the most considerable of which is that on the bay of Dundrum: part of this kind of soil is cultivated, part used as grazing land or rabbit-warren, and a small portion consists of shifting sands, which have hitherto baffled all attempts at improvement. There is a small tract of land south of the Lagan, between Moira and Lisburn, which is very productive, managed with less labour than any of the soils above mentioned, and earlier both in seed-time and harvest. Gravelly soils, or those intermixed with water- worn stones, are scattered over a great part of the county. Moory grounds are mostly confined to the skirts of the mountains: the bogs, though numerous, are now scarcely sufficient to afford a plentiful supply of fuel; in some parts they form the most lucrative portion of the property. The rich and deep loams on the sides of the larger rivers are also extremely valuable, as they produce luxuriant crops of grass annually without the assistance of manure.

The great attention paid to TILLAGE has brought the land to a high state of agricultural improvement. The prevailing corn crop is oats, the favourite sorts of which are the Poland, Blantyre, Lightfoot, and early Holland; wheat is sown in every part, and in Lecale is of excellent quality, and very good also in Castlereagh barony; barley is a common crop, mostly preceded by potatoes, rye is seldom sown, except on bog. Much flax is cultivated, and turnips, mangel-wurzel, and other green crops, are now very general. Though, from the great unevenness of surface, considerable tracts of flat pasture land are very uncommon, yet on the sides of the rivers there are excellent and extensive meadows, annually enriched by the overflowing of the waters; and, in the valleys, the accumulation of the finer particles of mould washed down from the sides of the surrounding hills, produces heavy crops of grass. Many of the most productive meadows are those which lie on the skirts of turf-bogs, at the junction of the peat and loam; the fertility of the compound soil is very great, the vegetation rapid, and the natural grasses of the best kind. Artificial grasses are general; clover is in frequent cultivation, particularly the white. Draining is extensively and judiciously practised, and irrigation is successfully resorted to, especially upon turf-bog, which, when reclaimed, is benefited by it in an extraordinary manner. In the management of the dairy, butter is the chief object, considerable quantities are sold fresh in the towns, but the greater part is salted, and sent to Belfast and Newry for exportation. Dung is the manure principally applied for raising potatoes, and great attention is paid by the farmers to collect it, and to increase its quantity by additional substances, such as earth, bog soil, and clay. Lime, however, is the general manure. At Ballinahinch, the central part of the county, limestone of three kinds may be seen in use by the farmers at a small distance from each other, the blue brought from Carlingford, the red from Castlespie, and the white from Moira, a distance of fourteen miles, the white is most esteemed. Limestone-gravel is used in the neighbourhood of Moira, and found to be of powerful and lasting efficacy. Marling was introduced into Lecale about a century ago: the result of the first experiments was an immediate fourfold advance in the value of land, and the opening of a corn-trade from Strangford; but the injudicious use of it brought it into discredit for some time, though it has latterly, under better management, resumed its former character. Shell-sand is used to advantage on stiff clay lands; and sea-weed is frequently applied to land near the coast, but its efficacy is of short duration. Turf-bog, both by itself and combined with clay, has been found useful. The system of burning and paring is practised only in the mountainous parts. In the neighbourhood of towns, coal-ashes and soot are employed: the ashes of bleach-greens, and soapers’ waste, have been found to improve meadows and pastures considerably. The attention of the higher class of farmers has been for many years directed to the introduction of improved implements of husbandry, most of which have had their merits proved by fair trial: threshing-machines are in general use. In no part of the country is the art of raising hedges better understood, although it has not yet been extended so universally as could be desired. In many parts the enclosure is formed of a ditch and a bank, from four to eight feet wide, and of the same depth, without any quicks, sometimes it is topped with furze, here called whins. In the mountainous parts the dry-stone wall is common.

The Cattle being generally procured more for the dairy than for feeding, special attention has not hitherto been paid to the improvement of the breed: hence there is a mixture of every kind. The most common and highly esteemed is a cross between the old native Irish stock and the old Leicester long-horned, which are considered the best milchers. But the anxiety of the principal resident landowners to improve every branch of agriculture having led them to select their stock of cattle at great expense, the most celebrated English breeds are now imported; and the advantages are already widely diffusing themselves. The North Devon, Durham, Here-ford, Leicester, and Ayrshire breeds have been successively tried, and various crosses produced; that between the Durham and Leicester appears best adapted to the soil and climate, and on some estates, there is a good cross between the Ayrshire and North Devon. But the long-horned is still the favourite breed of the small farmer. Great improvements have also been made in the breed of Sheep, particularly around Hillsborough, Seaford, Downpatrick, Bangor, Cumber, Saintfield, and other places, where are several fine flocks, mostly of the new Leicester breed. In other parts there is a good cross between the Leicester and old native sheep. The latter have undergone little or no change in the vicinity of the mountains; they are a small hardy race, with a long hairy fleece, and black face and legs, some of them horned; they are prized for the delicacy and flavour of their mutton. The breed of Pigs has of late been very much improved: the Berkshire and Hampshire prevail; but the most profitable is a cross between the Dutch and Russian breeds, which grows to a good size, easily fattens, and weighs well. The greater number are fattened and slaughtered, and the carcasses conveyed either to Belfast or Newry for the supply of the provision merchants, where they are mostly cured for the English market. The breed of Horses, in general, is very good. There are some remains of ancient woods near Downpatrick, Finnebrogue, Bryansford, and Castle-wellan; and the entire county is well wooded. The oak everywhere flourishes vigorously, in the parks of the nobility and gentry there is a great quantity of full-grown timber, and extensive plantations are numerous in almost every part, particularly in the vale of the Lagan from Belfast to Lisburn, and around Hollywood.

The geology of the county may now be noticed. The Morne mountains, extending from Dundrum bay to Carlingford bay, form a well-defined group, of which Slieve Donard is the summit, being, according to the Ordnance survey, 2796 feet above the level of the sea, and visible, in clear weather, from the mountains near Dublin. Granite is the prevailing constituent of the group. To the north of these mountains, Slieve Crooh, composed of sienite, and Slieve Anisky, of hornblende, both in Lower Iveagh, constitute an elevated tract dependent upon, though at some distance from, the main group. Hornblende and primitive greenstone are abundant on the skirts of the granitic district. Mica-slate has been noticed only in one instance. Exterior chains of transition rocks advance far to the west and north of this primitive tract, extending west-ward across Monaghan into Cavan, and on the north-east to the southern cape of Belfast lough, and the peninsula of Ardes. The primitive nucleus bears but a very small proportion, in surface, to these exterior chains, which are principally occupied by greywacke and greywacke-slate. In the Morne mountains and the adjoining districts an extensive formation of granite occurs, but without the varieties found in Wicklow, agreeing in character rather with the newer granite of the Wernerians; it constitutes, as already observed, nearly the whole mass of the Morne mountains, whence it passes across Carlingford bay into the county of Louth. On the north-west of these mountains, where they slope gradually into the plain, the same rock reaches Rathfriland, a table-land of inconsiderable elevation. Within the boundaries now assigned, the granite is spread over a surface of 324 square miles, comprehending the highest ground in the north of Ireland. Among the accidental ingredients of this formation are, crystallised hornblende, chiefly abounding in the porphyritic variety, and small reddish garnets in the granular: both varieties occur mingled together on the top of Slieve Donard. Water-worn pebbles, of porphyritic sienite, occasionally containing red crystals of felspar and iron pyrites, are very frequent at the base of the Morne mountains, between Rotsrevor and New-castle: they have probably been derived from the disintegration of neighbouring masses of that rock, since, on the shore at Glassdrummond, a ledge of porpbyritic sienite, evidently connected with the granitic mass of the adjoining mountain, projects into the sea. Green-stone-slate rests against the acclivities of the Morne mountains, but the strata never rise high, seldom exceeding 500 feet. Attempts have been made to quarry it for roofing, which it is thought would have been successful if they had been carried on with spirit. Felspar porphyry occurs in the bed of the Finish, north-west of Slieve Croob, near Dromara, and in a decomposing state at Ballyroney, north-east of Rathfriland. Slieve Croob seems formed, on its north east and south-east sides, of different varieties of sienite, some of them porphyritic and very beautiful: this rock crops out at intervals from Bakaderry to the top of Slieve Croob, occupying an elevation of about 900 feet.

Greymacke and Greywarke-slate constitute a great part of the baronies of Ardes, Castlereagh, and the two Iveaghs: the rock is worked for roofing at Bally al wood in the Ardes; and a variety of better quality still remains undisturbed at Cairn Garva, south-west of Conbigg HilL. Lead and Copper ores have been found in this formation at Conbigg Hill, between Newtown-Ardes and Bangor, where a mine is now profitably and extensively worked. Two small Limestone districts occur, one near Downpatrick on the south-west, and the other near Comber on the north-west, of Strangford lough. The Old Red-Sandstone has been observed on the sides of Strangford lough, particularly at Scrabo, which rises 483 feet above the lough, and is capped with greenstone about 150 feet thick; the remaining 333 feet are principally sandstone, which may be observed in the White quarry in distinct beds of very variable thickness, alternating with greywacke. This formation has been bored to the depth of 500 feet on the eastern side of Strangford lough, in the fruitless search for coal. which depth, added to the ascertained height above ground, gives from 800 to 900 feet as its thickness. The greatest length of this sandstone district is not more than seven miles; it appears to rest on greywacke. Coal, in three seams, is found on the shores of Strangford, and two thin seams are found under the lands of Wilmount, on the banks of the Lagan; there are also indications at coal, in two places near Moira. Chalk appears at gheralin, near Moira, proceeding thence towards the White mountains near Lisburn, and forming a low table- land. The quarries chiefly worked for Freestone are those of Scrabo and Kilwarlin, near Moira, at the latter of which flags are raised of great size, and of different colours from a clear stone-colour to a brownish red. Slates are quarried on the Ardes shore, between Bangor and Ballywalter, and near Hillsborough, Anahilt, and Ballinahinch: though inferior to those imported from Wales in lightness and colour, they exceed them in hardness and durability. In the limestone-quarries near Moira, the stone is found lying in horizontal strata intermixed with flints, in some places stratified, and in others in detached pieces of various forms and sizes; it is common to see three of these large flints, like rollers, a yard long and twelve inches each in diameter, standing perpendicularly over each other, and joined by a narrow neck of limestone, funnel-shaped, as if they had been poured when in a liquid state into a cavity made to receive them. Shells of various kinds are also found in this stone.

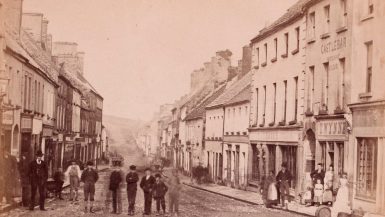

The staple manufacture is that of linen, which has prevailed since the time of William III., when legislative measures were enacted to substitute it for the woollen manufacture. Its establishment here is directly owing greatly to the settlement of a colony of French refugees, whom the revocation of the edict of Nantes bad driven from their native country, and more especially to the exertions of one of them, named Crommelin, who, after having travelled through a considerable part of Ireland, to ascertain the fitness of the country for the manufacture, settled in Lisburn, where he established the damask manufacture, which has thriven there ever since. The branches now carried on are, fine linen, cambrics, sheetings, drills, damasks, and every other description of household linen. Much of the wrought article, particularly the finer fabrics, is sent to Belfast and Lurgan for sale, the principal markets within the county are, Banbridge for finer linens, and Rathfriland, Downpatrick, Castlewellan, Ballinabinch, Newry, Dromore, and Kirkcubbin, for those of inferior quality. The cotton manufacture has latterly made some progress here; but as the linen-weavers can work at a cotton-loom, and as the cotton-weavers are unqualified to work at linen, the change has not been in any great degree prejudicial to the general mass of workmen in linen, who can now apply themselves to one kind when the demand for the other decreases. The woollen manufacture is confined to a coarse cloth made entirely for domestic consumption, with the exception of blanketing, which was formerly carried on with much spirit and to a greater extent, particularly at Lam beg. The weaving of stockings is pretty generally diffused, but not for exportation. Tanning of leather is carried on largely: at Newry is a considerable establishment for making spades, scythes, and other agricultural implements and tools; and there are extensive glass-works at Newry and Ballymacarrett. Kelp is made along the coast and on Strangford lough, but its estimation in the foreign market has been much lowered by its adulteration during the process. There is a considerable fishery at Bangor, for flat-fish of all kinds, and for cod and oysters; also, at Ardglass for herrings, and at Killough for haddock, cod, and other round fish. The smaller towns on the coast are also engaged in the fishery, particularly that of herrings, of which large shoals are taken every year in Strangford lough, but they are much inferior in size and flavour to those caught in the main sea. Smelts are taken near Portaferry, mullet, at the mouth of the Quoile river, near Downpatrick, sand-eels, at New-castle; shell-fish, about the Copeland Islands; and oysters, at Ringhaddy and Carlingford; those of the latter place being of very superior quality.

The principal rivers are the Bann and the Lagan: the former has its source in two neighbouring springs in that part of the mountains of Morne called the Deer’s Meadow, and quits this county for Armagh, which it enters near Portadown, where it communicates with the Newry canal. The Lagan has also two sources, one in Slieve Croob, and the other in Slieve-na-boly, which unite near Waringsford; near the Maze it becomes the boundary between the counties of Down and Antrim, in its course to Carrickfergus bay. There are also the Newry river and the Ballinahinch river, the former of which rises near Rathfriland, and falls into Carlingford bay; while the latter derives its source from four small lakes, and empties itself into the south-western branch of Strangford lough. The county enjoys the benefit of two canals, viz., the Newry navigation, along its western border, connecting Carlingford bay with Lough Neagh, and the Lagan navigation, which extends from the tide-way at Belfast along the northern boundary of the county, and enters Lough Neagh near that portion of the shore included within its Omits. The Lagan line originated in an act passed in the 97th of George II.: its total length is 10 miles; but, from being partly carried along the bed of the Lagan, its passage is so much impeded by floods as to detract much from the benefits anticipated from its formation. The introduction of railways has also tended to diminish the value of the canal property.

Among the antiquities are two remarkable Cairns; one of them on the summit of Slieve Croob, measuring 80 yards round at the base and 50 on the top, and forming the largest monument of the kind in the county: on this platform several smaller cairns are raised, of various heights and dimensions. The other is near the village of Anadorn, and is more curious, from containing within its circumference, which is about 60 yards, a large square smooth stone supported by several others, so as to form a low chamber, in which, on examination, were found ashes and some human bones. A solitary pillar stone stands on the summit of a hill near Saintfield, having about six feet of its length above the ground. Among the more remarkable Cromlechs is that near Drumbo, called the Giant’s Ring; also, one on Slieve-na-Griddal, in Lecale: there is another near Sliddery ford, and a fourth is in the parish of Drumgooland, others less remarkable may be seen near Rathfriland and Comber. There are two Round Toweri; one stands about 24 feet south-west of the ruins of the church of Drumbo, and the other is close to the ruins of the old church of Maghera: a third, distinguished for the symmetry of its proportions, stood near the cathedral at Downpatrick, but it was taken down in 1790, to make room for rebuilding part of that edifice. Of the relics of antiquity entirely composed of earth, every variety is to be met with. Raths surrounded by a slight single ditch are numerous, and so situated as to be generally within view of each other. Of the more artificially constructed mounds, some, as at Saintfield, are formed of a single rampart and fosse; others may be seen with more than one, as that at Downpatrick, which is about 895 yards in circuit at the base, and surrounded by three ramparts. A third kind, at Dromore, has a circumference of 600 feet, with a perpendicular height of 40 feet; the whole being surrounded by a rampart and embattlement, with a trench that has two branches embracing a square foot, 100 feet in diameter: and there are other mounds very lofty at Donaghadce and Dundonald, with caverns or chambers running entirely round their interior. A thin plate of gold, shaped like a half moon, has been dug out of a bog in Castlereagh; the metal is remarkably pure, and the workmanship good, though simple. Another relic of the same metal, consisting of three thick wires intertwined through each other, and conjectured to have formed part of the branch of a candlestick, has been discovered near Dromore. Near the same town have been found a canoe of oak, about 13 feet long, and various other relics; another canoe was found at Lough-brickland, and a third in the bog of Moneyreagh. An earthen lamp of curious form was dug up near Moira, the figures on which were more remarkable for their indecency than their elegance.

There are numerous remains of monastic edifices. the principal is those at Downpatrick, those of Grey Abbey on the shore of Strangford lough, at Moville near New-town-Ardes, Inch or Innis Courcy near Downpatrick, Newry, Black Abbey near Bally halbert, and Castlebony, or Johnstown in the Ardes. The castles are also worthy of attention. The first military work which presents itself in the southern extremity of the county is Greencastle, on the shore of Carlingford bay, said to have been built by the De Burgos, and afterwards commanded by an English constable, who also had charge of Carlingford Castle: these two were considered as out-works of the pale, and therefore intrusted to none but those of English birth. The castle of Narrowwater is of modern date, having been built by the Duke of Ormonde after the Restoration. Dundrum Castle is finely situated upon a rock overlooking the whole bay to which it gives name; it was built by De Courcy for the Knights Templars, but afterwards fell into the hands of the Magennis family. Ardglass, though but a small village, has the remains of considerable fortifications; the ruins of four castles are still visible. Not far from it is kilclief Castle, once the residence of the bishops of Down; between Killough and Downpatrick are the ruins of Bright and Screen Castles, the latter built on a Danish rath, as is that of Clough; in Strangford lough are Strangford Castle, Audley’s Castle, and Walsh’s Castle; Portaferry Castle, in the Ardes, was the ancient seat of the Savages, in the Ardes are also the castles of Quintin, Newcastle, and Kirkestown; the barony of Castlereagh is so called from a castle of the same name, built on a Danish fort, the residence of Con O’Neill; near Drumbo is Hill Hall, a square foot with flanking towers; Killileagh Castle is now the residence of the family of Rowan; and at Rathfriland are the ruins of a second castle of the Magennises. General Monk erected forts on the passes of Scarva, Poyntz, and Tuscan, which connect this county with Armagh, the ruins still exist. At Hillsborough is a small castle, maintained in its ancient state by the Marquess of Downshire, hereditary constable; and other castles in various parts have been taken down. The gentlemen’s scats are numerous, and many of them built in a very superior style; the chiefs are noticed in their respective parishes.

Mineral springs, both chalybeate and sulphureous, abound, but the former is the more numerous. Of the chalybeate springs, the most remarkable are, Ardmillan, on the borders of Strangford lough; Granshaw, in the Ardes, Dundonald, three miles north-west of Newtown-Ardes Magheralin, Dromore, Newry, Banbridge, and Tierkelly. Granshaw is the richest, being equal in efficacy to the strongest of the English spas. The principal sulphureous spa is near Ballinahinch: there is an alum spring near the town of Clough. The Struelsprings, situated one mile south-east of Downpatrick, in a retired vale, are celebrated not only in the neighbourhood and throughout Ireland, but in many parts of the continent, for their supposed healing qualities, arising not from their chemical but their miraculous properties: they are dedicated to St. Patrick, and are four in number, viz., the drinking well, the eye well, and two bathing wells, each enclosed with an ancient building of stone. The principal period for visiting them is at St. John’s eve, on which occasion the water rises in the wells, supernaturally, according to the belief of those who visit them. Penances and other religious ceremonies, consisting chiefly of circuits made round the wells for a certain number of times, together with bathing, accompanied by specified forms of prayer, are said to have been efficacious in removing obstinate and chronic distempers. A priest formerly attended from Downpatrick, but latterly the visits to these wells have been discountenanced by the Roman Catholic bishop of the diocese. Not far distant are the walls of a ruined chapel, standing north and south; the entrance was on the north, and the building was lighted by four windows in the western wall. St. Scorden’s well, in the vicinity of Killough, is remarkable from the manner in which the water gushes out of a fissure in the face of a rock, on an eminence close to the sea, in a stream which is never observed to diminish in the driest seasons.

Pearls bare been met with in the bed of the Bann river. Fossil remains of moose-deer have been found at different places; and various kinds of trees are frequently discovered imbedded in the bogs. This county is remarkable as being the first place in Ireland in which frogs were seen: they appeared originally near Moira, in a western and inland district, but the cause or manner of their introduction is wholly unknown. The Cornish chough and the king-fisher have been occasionally met with near Killough; the bittern is sometimes seen in the marshes on the sea-coast; the ousel and the eagle have been observed in the mountains of Morne, and the cross- bill at Waringstown. Barnacles and widgeons frequent Strangford lough and Carrickfergus bay in immense numbers during winter; but they are extremely wary. A marten, as tall as a fox, but much longer, was killed several years since at Moira, and its skin preserved as a curiosity. Horse-racing is a favourite amusement with all classes, and is here sanctioned by royal authority; James II. having granted a patent of incorporation to a society to be called the “Royal Horse breeders of the County of Down,” which is still kept up by the resident gentry, and has produced a beneficial effect in improving the breed of race-horses. Downshire gives the title of Marquess to the family of Hill, the descendants of one of the military adventurers who came to Ireland in the reign of Elizabeth.

Leave a reply