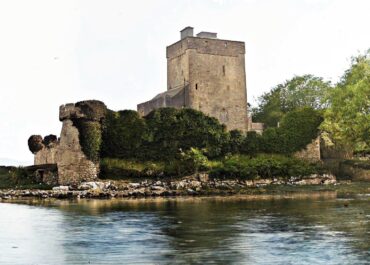

Bawn, Fahee North, Co. Clare

On a gentle rise in the semi-karst landscape of Fahee North, County Clare, the remains of a substantial bawn tell a story of defensive architecture that spans centuries.

Bawn, Fahee North, Co. Clare

This irregular, diamond-shaped fortification stretches approximately 84 metres from north-northwest to south-southeast and 60 metres at its widest point. The mortared stone walls, roughly a metre thick and standing about two metres high in places, still retain evidence of their defensive purpose; a high parapet on the western wall contains three narrow shot-holes, whilst square platforms in the western and southeastern corners mark where corner turrets once stood guard. Multiple gateways pierce the walls, with substantial piers flanking entrances on the northeast and southeast sides, and narrower gaps to the west and north.

Within these weathered walls lies a complex of medieval structures that speak to centuries of habitation and modification. A tower house, now poorly preserved, occupies the northwestern centre of the enclosure, whilst two medieval houses also shelter within the bawn’s protective embrace. One of these houses, built against the inner face of the bawn wall to the southwest, incorporates crude cantileveral steps that were also partly built into the wall itself, suggesting the house and bawn were constructed simultaneously. Throughout the eastern section of the interior, small earthworks and rubble mounds hint at additional buildings and dividing walls that once organised this fortified space, whilst a circular stone structure, possibly a well, adds to the site’s domestic features.

The bawn’s complex history has sparked intriguing theories about its evolution. Vestiges of a wide wall running through the centre of the enclosure may represent an earlier eastern boundary, suggesting the fortification was expanded at some point in its history. Local tradition, recorded in 1839, maintains that this wasn’t a typical castle but rather served as a large house or garrison. The presence of shot-holes, corner turrets, and multiple gateways has led some historians to propose that the expanded defensive bawn might date to the Cromwellian period between 1653 and 1660, when such garrison fortifications were strategically important. Despite its ruined state, marked on Ordnance Survey maps as early as 1842, this atmospheric site continues to reveal layers of Irish military and domestic architecture across its windswept rise.