Historic town, Donegal Town, Co. Donegal

The town of Donegal sits at the head of Donegal Bay, overlooking the broad, shallow estuary where the River Eske meets the sea.

Historic town, Donegal Town, Co. Donegal

Its name comes from Dún na nGall, meaning “fort of the foreigners”, likely referring to Vikings who raided these shores in the 9th and 10th centuries, though no trace of their settlement has ever been found. The town truly came into its own during the late medieval period as a stronghold of the O’Donnell lords of Tirconnell. Hugh Roe O’Donnell built the impressive castle around 1474, establishing a Franciscan friary nearby at roughly the same time. When Sir Henry Sidney visited in 1566, he declared the castle “one of the greatest that ever I saw in Ireland in any Irishman’s lands”, praising its strategic position so close to navigable waters that boats could sail within twenty yards of its walls.

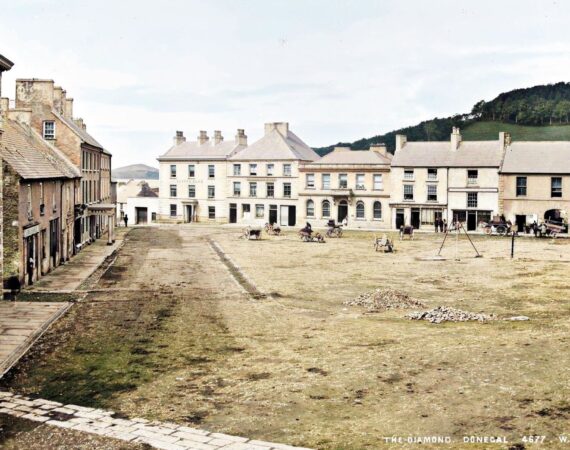

The turbulent years of English conquest transformed Donegal dramatically. After being burned in 1588 to prevent English occupation, then rebuilt and lost again during the Nine Years’ War, the town finally fell under English control following the Flight of the Earls in 1607. Captain Basil Brooke received the land grant and set about creating a planned plantation town. By 1611, he’d built a fortified bawn with fifteen foot high walls, and settlers were constructing “good copled houses after the manner of the Pale”; some half-timbered, others built of stone. The town received its charter in 1613, with market rights for Thursdays and an annual fair on St Peter’s feast day. Brooke laid out the settlement around a triangular market square known as the Diamond, with three streets radiating from it: Bridge Street, Main Street, and Quay Street, a pattern that still defines the town centre today.

Archaeological excavations have revealed glimpses of Donegal’s maritime past beneath the modern streets. Near Quay Street, archaeologists uncovered an early quay wall built directly against bedrock steps, its water-facing side crafted from large, finely wrought stone blocks. This appears to be the town’s first quay structure, later hidden behind 18th-century reclamation works as the harbour expanded. Despite burning by Jacobite forces in 1689 and centuries of development, the town retains its plantation-era street plan and burgage plot patterns, visible reminders of its transformation from a Gaelic lordship’s seat to an English colonial town.