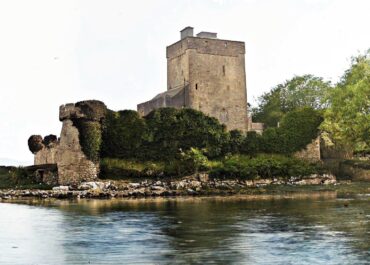

Shallee Castle, Shallee, Co. Clare

Shallee Castle stands at the northern end of a rocky outcrop in County Clare, its remaining walls telling a tale of centuries of ownership disputes and political upheaval.

Shallee Castle, Shallee, Co. Clare

The castle’s turbulent history began in 1574 when it belonged to Brian dubh O’Brien, grandson of Conor na Srona O’Brien, King of Thomond. After Brian lost his possessions following the Battle of Rath in 1562, he managed to secure a pardon by 1569 and regain his lands. The castle then passed to his descendant Donough Ganach, whose son Turlough met a grim fate; hanged for treason in 1591, resulting in the forfeiture of Shallee to Thomond Morrice. Yet by 1603, Conor, son of Donough Ganach, had somehow reclaimed possession. The subsequent decades saw a revolving door of owners and tenants, from Francis Chamberlain in 1606 to Patrick O’Hogan in 1641, and eventually to Barnabas O’Brien, sixth earl of Thomond, after Murrough O’Brien, Baron Inchiquin, forfeited his lands during the 1641 rebellion.

What remains today is a partial four-storey tower house, with only the south wall and sections of the east and west walls still standing. The structure showcases medieval building techniques, including a ground floor barrel vault constructed with wicker centering and flat-arch embrasures using plank centering. The upper floors featured lintelled embrasures with simple window lights, whilst the third floor boasted more elaborate twin-light ogee-headed windows with square hood moulding in the south wall. Notably absent are any surviving entrances, stairs, garderobe chutes or chimneys, suggesting these essential features were located in the now-missing northern portions of the building.

The castle’s builders quarried stone directly from the area south of the tower, creating a defensive dry moat measuring 9 metres wide and 2.7 metres deep that curves from southeast to southwest. The rock outcrop extends about 2 metres around each side of the tower house, with remnants of a wall foundation visible on the eastern side. Though the castle likely fell into disrepair by the mid-17th century, records show it remained noted as O’Brien property in documents from 1706, 1709 and 1763, a testament to the enduring significance of land ownership even when the structures themselves had crumbled.